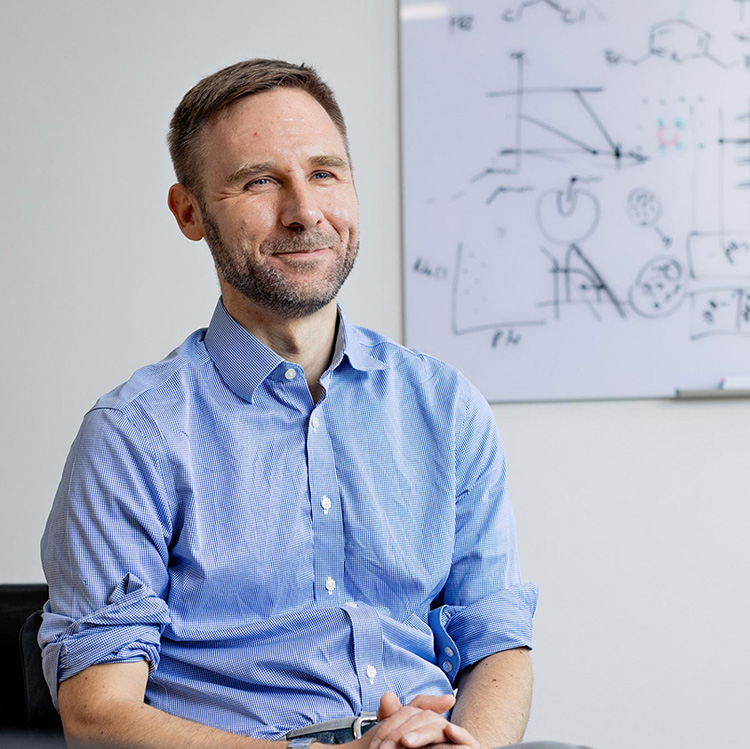

In the latest of the University’s Enterprising Minds series, Professor Tuomas Knowles reflects on turning pioneering protein science into ventures that tackle global challenges in health and sustainability.

The Enterprising Minds series, developed by Sarah Fell with the help of Bruno Cotta, Visiting Fellow & Honorary Ambassador at the Cambridge Judge Business School, explores the different journeys of people trying to change the world and what it takes to bring ideas to life.

WHO?

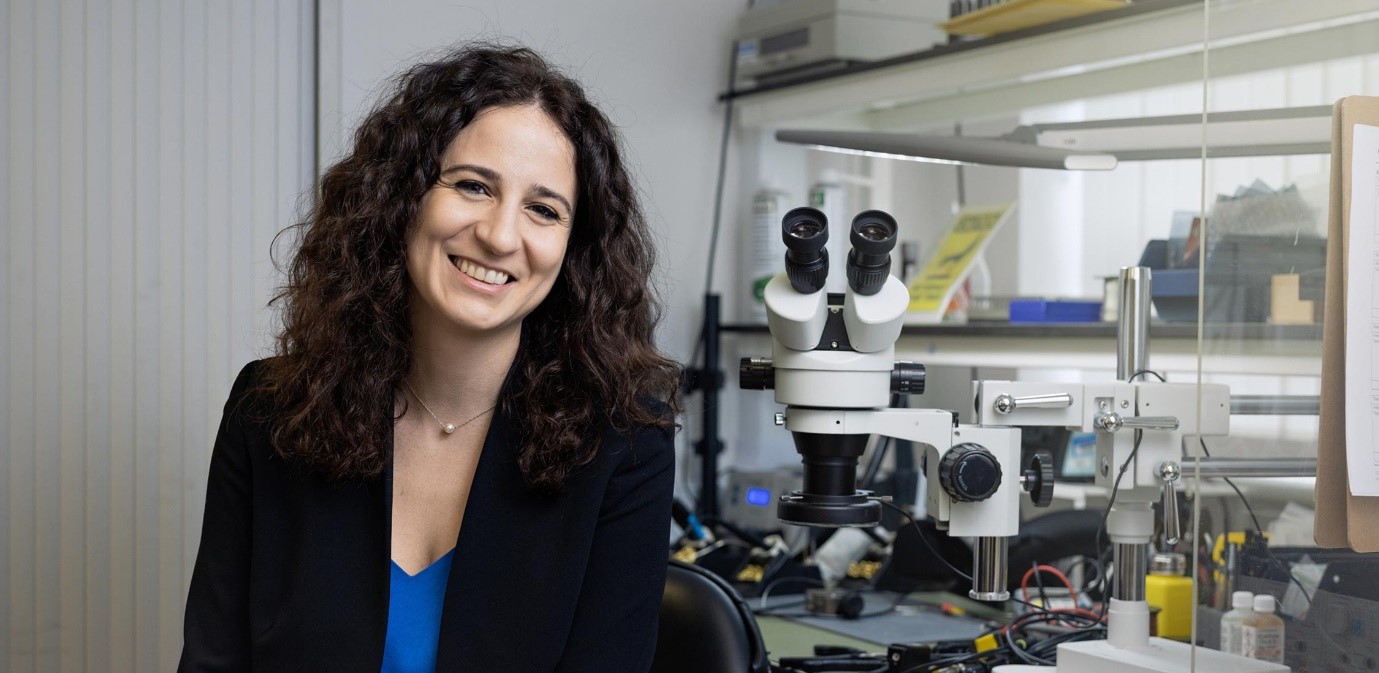

Professor Tuomas Knowles, world-leading expert on proteins and founder of five spinout companies, all of which apply breakthroughs in protein science to real-world problems.

WHAT?

Xampla is replacing the most polluting plastics with plant-based materials; Transition Bio applies fundamental biology to drug discovery; Ride Therapeutics develops solutions for organ-specific gene delivery; WaveBreak Therapeutics (formerly Wren Therapeutics) develops treatments for neurodegenerative diseases and Fluidic Sciences (formerly Fluidic Analytics) creates tools to help scientists understand how proteins interact.

WHY?

“To solve some of the fundamental problems we face today in both human and planetary health.”

What set you off on the commercialisation path?

I’ve always been interested in research which address key societal issues. We’ve found there are two ways to do this: the first is to work with established companies and we’ve got some exciting collaborations with industry partners, including many of the leading pharma companies.

We really like working in that way: we bring something and they bring something and together we move forward.

Sometimes, particularly when you are dealing with fundamentally new technologies, the work we carry out at the University is not yet at a stage where industry partners can engage with it directly.

You have to do a lot of the legwork yourself in order to get it to a point where it’s scalable. In these situations, we find that founding a spinout company works very well.

Do you enjoy the process of founding companies?

Definitely. Starting a company is a particularly exciting activity. Obviously, the science and technology aspects are fascinating but so are the people. It’s fantastic to try to assemble a team not just of scientists but also of people who understand the business side of things.

You are now on your fifth company. Is there anything you wished you’d known when embarking on the first?

Only that the advice you get given is mostly true. At the end of the day, it’s all about getting the right people on board.

It’s so much fun when you are working with people who are absolutely at the top of their game. It would also be good to know that it’s very time consuming and does slightly end up taking over your life – but it is fun!

“It's so much fun when you are working with people who are absolutely at the top of their game.”

Do you see yourself as a scientist, an entrepreneur or a scientific entrepreneur?

My contribution is mainly on the science and technology side and how technological advances open up particular markets and how we might scale them.

So it’s still very much science and technology-focused. And, of course, I spend the majority of my time leading my research group in the University, thinking about the fundamental research and how can we push the boundaries of understanding biomolecular systems.

Things are changing very rapidly in this area right now. There’s been something like 50 years of modern protein science, much of which has, in fact, taken place in Cambridge. Until now, as a community, we’ve focused on understanding individual molecules, how proteins fold, misfold and what kind of shapes they take and the characteristics they display.

But it turns out that most proteins are ‘sociable’ molecules. They like to interact with other proteins and do things together.

It’s very clear to me that the next 50 years of protein science will not be about individual molecules but rather about molecular systems which is the level at which function and malfunction emerge.

It’s such an exciting time for the fundamental science: we’re continuously learning new things and discovering completely new principles. And this has important implications for human and planetary health and for materials science.

“It’s such an exciting time for the fundamental science.”

Which of your spinouts are you most excited about right now?

I’ll start with Xampla which stemmed from my lab’s fascination with spider silk, a material which is – weight for weight – stronger than steel, yet immensely elastic.

Perhaps the most intriguing thing about it is that it’s made with minimal energy. Dining on just one fly will enable the spider to produce its silk at room temperature, with almost no waste. This is the dream for sustainability, right?

As scientists, we wanted to understand first how it works and, once we’d done that, if we could tweak it or even replicate it. When it turned out we could, we started to wonder if it might be possible to replace single-use plastic packaging with materials which have similar properties but are made from purely natural proteins and are fully biodegradable.

But you can’t make a product in a university. It became apparent that to take this idea further we would need to start a company. We began with market research to really understand what was needed. The overwhelming consensus was that companies were looking for plant-based materials, ideally made from feedstocks which would otherwise be waste products.

Unfortunately, very little fundamental work had been done on the self-assembly of plant proteins. So Marc Rodriguez, our brilliant Chief Technology Officer, went back to the drawing board and spent a further year in the lab to understand the behaviour of some of the key plant proteins.

Fast forward to today and Xampla has brought to market a range of biodegradable plant-based packaging, materials including a world-first, plastic-free barrier coating for paper packaging.

What about your most recent spinout, Transition Bio?

This is an exciting collaboration with colleagues at Harvard University. Advances in microfluidics and microscopy mean that we are starting to understand more about the processes taking place in living cells and how they organise themselves.

One of the ways this happens is that if there are lots of what we call disordered proteins – proteins that lack a fixed structure – they act as ‘hubs’ to bring other proteins together. Often when things go wrong, it’s because one of these hubs has been assembled somewhere it’s not supposed to be.

We asked ourselves if we could better understand the rules by which these proteins assemble and talk to other proteins. If we could do that, we should be able to design molecules which corrects this assembly when it goes wrong.

Having developed the technology we needed to scale it up by bringing in people who understand how to take a molecule and turn it into a drug.

It was the natural next step to set up a company to move that technology forward with co-founders from Harvard and from School of Clinical Medicine here in Cambridge.

Has being in Cambridge helped get these new ventures off the ground?

Cambridge Enterprise has been incredibly supportive, particularly over questions of IP and how to protect it. We have also benefitted from its seed funding, which makes a huge difference in the very early stages.

Has the Cambridge innovation landscape changed over the last ten years?

It seems to me that what’s changed most is the interest of students in entrepreneurial activities.

Previously, I would have to explain to them why they might want to consider translational research and entrepreneurship whereas today’s students are well aware of the opportunities in innovation, which I think is a really positive development.

What are you most proud of?

I’m always most excited about what’s coming next and the huge potential we have to move these technologies forward.

Of the things we’ve done so far, what’s most satisfying is the journey from no idea to an idea in the lab and then to something that is out in the world, having a real impact on people’s lives.

I’m proud of that and I’m also proud of helping other people along the way. It’s fantastic when you see a group of people thriving. In short, I’m proudest of both the ideas and the people.

“What's most satisfying is the journey from no idea to an idea in the lab and then to something that is out in the world.”

Have you had any setbacks?

On some level, everything is difficult. With the science, you can normally work it out. Science and technology risks are something we understand and can manage.

Commercial risks are harder: you need the right people to manage them properly.

What would your colleagues say is your greatest strength?

I think they’d say that I’m passionate about science, about understanding how things work at the most fundamental level.

Do you have a piece of advice for someone thinking about starting a new venture?

Do it. It’s exciting. It’s fun. You’ll learn lots. Also, make sure you have the right people to help you on your journey.

With all this going on, do you have any spare time and, if so, how do you spend it?

Any spare time is spent with my wonderful family. Between the University, my research group here, helping the companies we’ve set up, and some of our industrial partners, I guess I don’t have that much genuinely free time.

But that’s my choice and it’s a privilege to be able to do something I’m passionate about.

Quick Fire

Optimist or pessimist? Definitely an optimist. When you see the progress we have already made and the potential for more, it’s hard not to be optimistic.

People or ideas? You need both, but it’s people who have the ideas, so I’d have to go with people.

On time or running late? I’d love to say on time, but the reality is running late.

The journey or the destination? With my fundamental scientist’s hat on, I love the journey. The destination is motivating and satisfying but the journey is so exciting.

Team player or lone wolf? The only way to make progress is with a team. And that team must have diversity of disciplines, of people and of thinking. It’s also more fun, by the way.

Risk-taker or risk averse? Risk-taker. You just can’t try new things if you don’t take risks. Not everything works out. But even when that happens you learn a lot.

Big picture or fine detail? I think you need both. The details have to work. But what gets me really excited is understanding how the details fit together to make the big picture.

Do you need to be lucky or do you make your own luck? Probably both. What is the quote that gets attributed to Louis Pasteur? ‘Luck favours the prepared mind’.

In my experience, the more you look into something, the more likely you are to understand how it works. And if you understand how it works, you can make useful progress.

Work, work, work or work-life balance? You need a work-life balance otherwise you’re not successful and happy in either. But that balance is different for everyone. I’m privileged to be involved in lots of really exciting activities and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

This interview was originally published as part of the University of Cambridge Enterprising Minds series, authored by Sarah Fell and developed with the help of Bruno Cotta, Visiting Fellow & Honorary Ambassador at the Cambridge Judge Business School.

The text in this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

All photography: StillVision