In this Enterprising Minds series, we interview with Sabine Bahn who is creating ways to take care of mental health through faster diagnosis and treatment.

The Enterprising Minds series, developed by Sarah Fell with the help of Bruno Cotta, Visiting Fellow & Honorary Ambassador at the Cambridge Judge Business School, explores the different journeys of people trying to change the world and what it takes to bring ideas to life.

WHO?

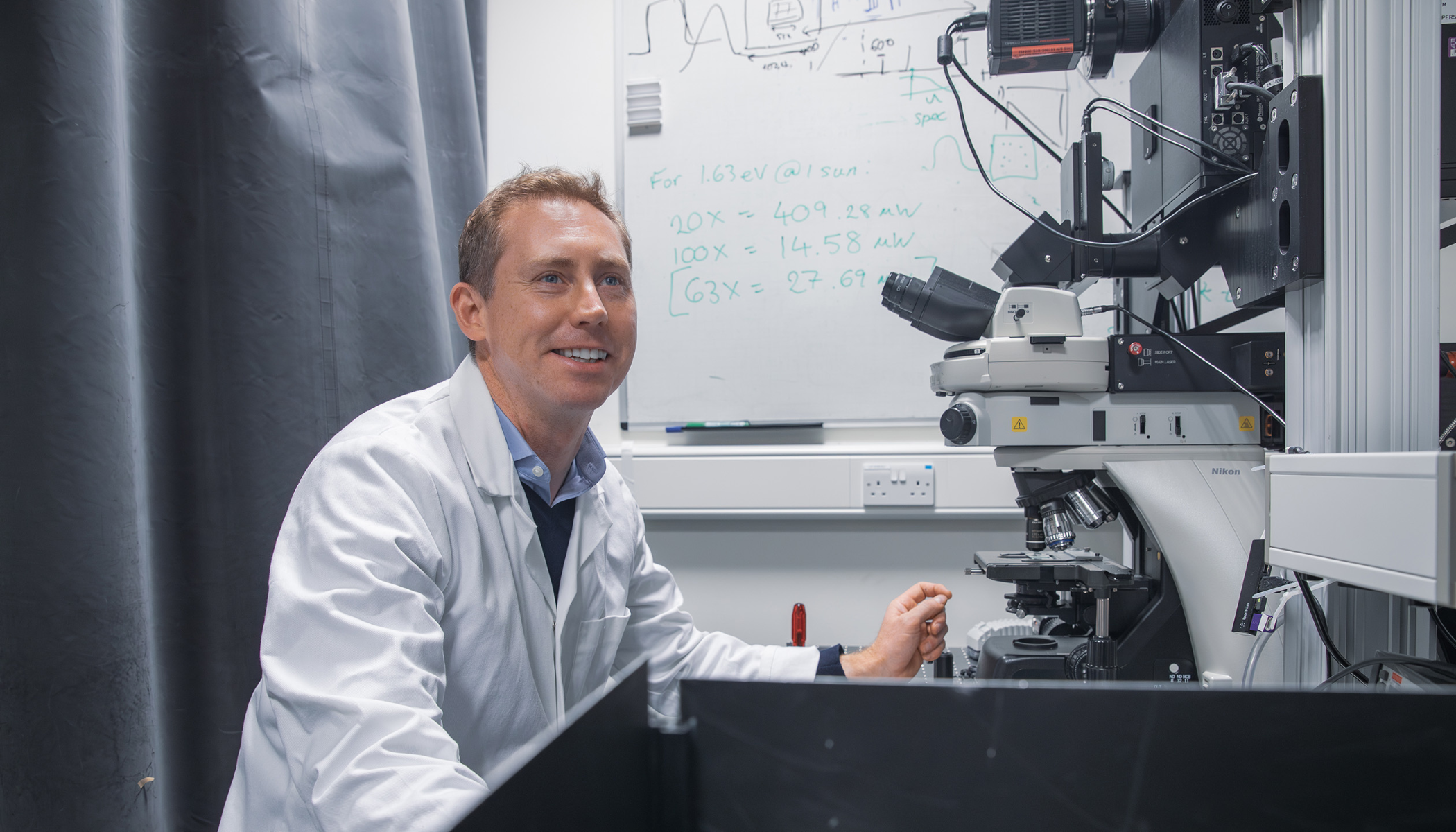

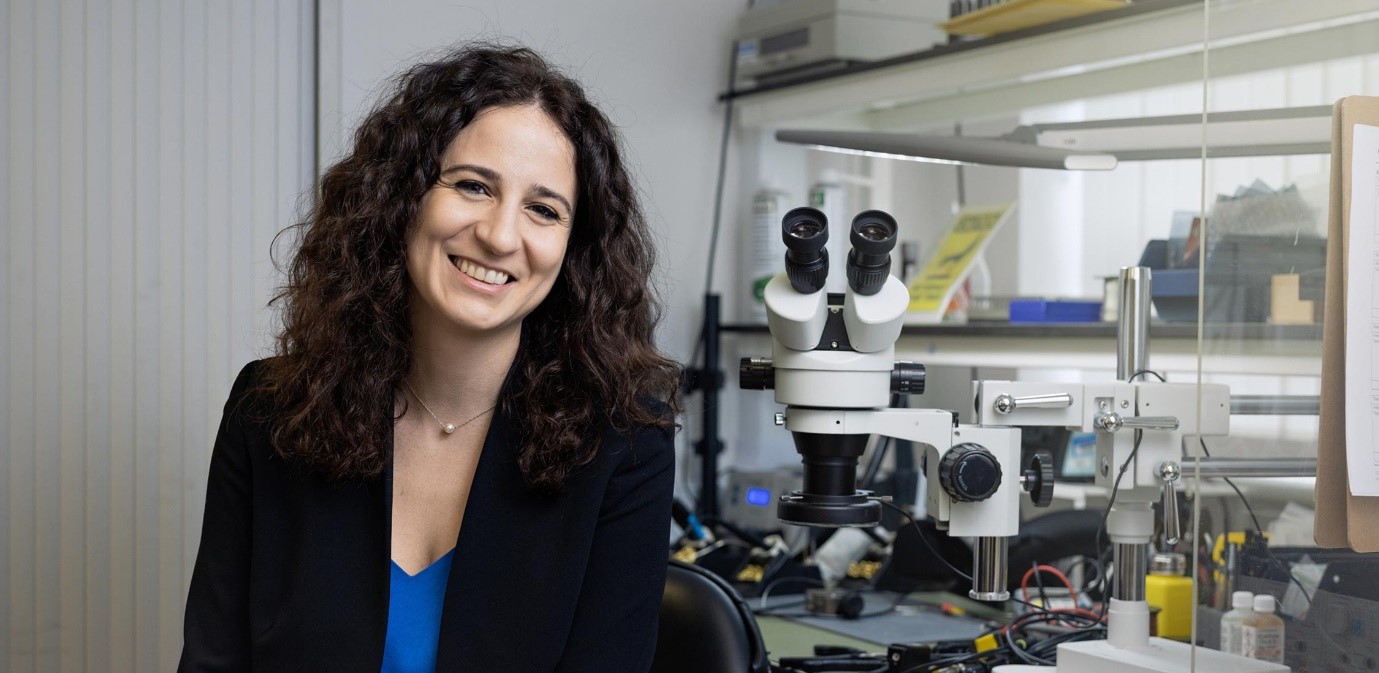

Sabine Bahn is a practicing psychiatrist, Professor of Neurotechnology and head of the Cambridge Centre for Neuropsychiatric Research. She has also found the time to start two companies.

WHAT?

Her first company, Psynova (acquired by Myriad Genetics in 2011), developed a blood test to diagnose psychiatric conditions, particularly schizophrenia. In 2015, she co-founded Psyomics to help patients get a rapid diagnosis of their mental health disorders. Its digital platform, Censeo, is already used by two NHS trusts and has assessed more than 1,000 patients to date.

WHY?

“The way in which we diagnose psychiatric disorders has not changed in the last 100 years. We need to find a better way of doing it so that the millions of people with mental health concerns do not struggle to access the treatment they need.”

How did you end up founding two companies?

It’s a long story and it goes back to my childhood. My father suffered from bipolar disorder but this was not explained to me when I was young. I found it confusing that he would switch from being one person to another and I’m sure that has played a part in my life choices, starting with my decision to study medicine at the University of Freiburg.

I was always interested in the brain. From the first year of my medical training – with the support of my professors – I would head off to labs between lectures to do my own research.

I became very interested in neuropathology and started an MD thesis on neuropsychiatric disorders from a neuropathology point of view. I was awarded a scholarship by the German National Scholarship Foundation which also allowed me to spend a year abroad.

I decided I wanted to spend that year at a particular lab in the world-famous LMB (Laboratory of Molecular Biology) in Cambridge. I emailed them numerous times and became very upset when they didn’t reply. I didn’t have a plan B.

Eventually, they answered my messages and I spent an inspirational year in Cambridge. There were four Nobel laureates working at the LMB at the time.

Afterwards, I went back to Germany to finish my medical training but came straight back to the LMB to do my PhD. I then had to decide whether to stay in science or go back to medicine.

A conversation with Sir Keith Peters, the then Regius Professor of Physic at Cambridge, steered me towards both neuropathology and psychiatry. The former I was very comfortable with but the latter was an unknown quantity.

Two fantastic psychiatrists allowed me to sit in their clinics for six months and I found it fascinating. I decided I would like to become a psychiatrist.

At the same time, I applied for funding to continue my research interests and I was lucky to get a small one-year grant from the Stanley Medical Research Institute which supports research into severe mental illness, particularly schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

“Everybody told me that I couldn’t possibly train as a psychiatrist and set up my own lab at the same time.”

Your combination of clinical practice and research interests must make you pretty unique?

Everybody told me that I couldn’t possibly train as a psychiatrist and set up my own lab at the same time.

I ignored them and started to research post-mortem brains of people with different psychiatric disorders. At the time, I was also doing 56 hours of clinical work a week, including a night on call. It was a very busy time but I had a lot of support from the head of department who gave me one day a week to focus on my research.

The Stanley Institute continued to fund my research on post-mortem brains. But after a couple of years, they said: “Sabine, it’s nice that you are doing this work and you are coming up with lots of interesting findings, but we would prefer it if you could research something which is more directly relevant to helping patients.”

From my clinical work, I could see how long it was taking for patients to get a diagnosis, something that is still largely arrived at by asking questions. Psychiatric evaluation is not an objective process and it can take a very long time for people to get the right diagnosis. I wanted to look for biological evidence of brain abnormalities which could provide an instant answer and get patients on the right pathway straightaway.

We found changes in the cerebral spinal fluid, and based on these findings I was funded to look for biomarkers for certain psychiatric conditions – particularly schizophrenia – with the hope of being able to develop early diagnostic tests.

When did you start to think about founding a company?

I began to explore the idea when we started to get positive results. I talked to Cambridge Enterprise but didn’t have any business experience and no real idea of how to go about it.

At around the same time, I made the decision to move my lab from Babraham and, with the support of the University, moved into what was then the Institute of Biotechnology (which has since merged with the Department of Chemical Engineering).

It was there I met Professor Chris Lowe who has been the driving force behind many Cambridge spinouts. He became the co-founder of Psynova and more or less took me by the hand and put me in touch with all the right people.

We got some grant money from the University to undertake a proof of concept study, followed by seed funding and then venture capital. And within five years we had some nice results.

Eventually we were acquired by Myriad Genetics, a NASDAQ-listed company. We did release a diagnostic blood test for schizophrenia, but unfortunately it has not survived into wider clinical application.

So it was a success in terms of entrepreneurship and having an exit, but it was a big disappointment that we weren’t able to develop something which ultimately helps patients.

But you didn’t give up on the idea?

No. I began to think about the limitations of the Psynova approach. The blood had to be collected from the vein, spun down and then shipped on dry ice. This cost a lot of money and the platform that we used was also very expensive. So each test cost $2,600 which is just too much to roll out widely for any healthcare provider – even a private one.

I wondered, instead, if it would be possible to identify biomarkers in dried blood spots which could be collected by the patients themselves and mailed in an envelope.

I went to see Cambridge Enterprise again and asked if they thought it would be worth starting another company to develop this new technology. They did.

However, the problem with biomarkers is even if they are highly sensitive, they produce high false positive and negative rates. But if you enrich that data with symptoms, you will get much more accurate results.

In conjunction with the dried bloodspots, therefore, we developed a digital platform which emulated a full psychiatric assessment, asking patients about their psychiatric history and personal circumstances.

Cambridge Enterprise gave us some seed funding to support a large-scale trial in collaboration with my lab. 1,300 people sent us their dried blood spots and completed the online assessment.

The results took us completely by surprise: the digital platform significantly outperformed the biomarkers. We decided to pivot and focus on the digital diagnosis instead.

Then COVID came along and our plans were delayed by a year to 18 months. But we are very fortunate that our investors have stood by us. They understood that we were operating in difficult circumstances and gave us more money and new investors came on board.

Where is Pysomics now?

We have launched our digital diagnostic platform, called Censeo. It is currently being used in two NHS trusts and we have our first paying customer – which is a major milestone.

“… a patient is sent to a particular service and, after a long wait, they are told they are too ill, or not ill enough, or the wrong type of ill and then they have to join a waiting list for a different service…”

Why is it needed?

There are not enough psychiatrists in the NHS: we all have too many patients and too long waiting lists. What often happens is that a patient is sent to a particular service and, after a long wait, they are told they are too ill, or not ill enough, or the wrong type of ill and then they have to join a waiting list for a different service.

This can happen over and over again, taking months and sometimes years before they end up in the right place and the patient has to retell their story every time and may not receive effective treatment.

By developing a platform which can assess large numbers of patients early on, we can direct them straightaway to the most appropriate intervention.

What about the biomarkers? Have you given up on those?

Not at all. We are continuing to work on them in the lab and we’re just filing another patent which will be licensed to the company.

What would you say are the greatest challenges you’ve faced in starting your companies?

There is always the potential for things to go pear-shaped – and plenty of times when they did.

When that happens you need people who can support you, who give you a shoulder to cry on. I was so lucky to have an inner circle of three or four people who have been by my side for decades. It’s almost like having a family.

How have they helped?

Sometimes you just want unconditional support but there are times when you need them to be critical – and you need to be able to accept that criticism.

After my first big conference presentation, one of my greatest supporters pulled me apart – legs, arms, everything. I trusted this person and allowed them to ‘destroy’ me and then put me back together.

After setbacks, you have to be able to pick yourself up, dust yourself down and keep on going. The other thing you need to be able to do, is to zigzag. You can never pursue an idea in a linear fashion. You have to be open to the idea that your original vision may turn into something completely different. I had set out to develop a blood test and never envisaged that we would have a digital platform instead.

“You have to be open to the idea that your original vision may turn into something completely different.”

Which aspects of founding companies have you most enjoyed?

Having the idea. I like developing the concept and then I need to hire excellent people to make it all happen. This was a problem with my academic career. Most academics are experts in a particular technique, whereas I’m interested in the vision and will use any tool I can lay my hands on to solve a problem. This is a very unacademic approach and as a result I’ve had a lot of headwind from other academics.

Have there been other challenges combining an academic career with founding companies?

As academics, we are measured by the number of papers we publish in the highest ranked journals. When I was doing pure research, I was publishing fantastic papers. But once you start doing more translational work, you have to do a lot of ‘handle turning’ because you need to optimise your approach. As a result, your papers become less exciting and are published in lower impact journals.

“I worked 80 to 90 hours a week for many years which meant having to sacrifice – or at least postpone – some personal things.”

Do you have any advice for someone who is thinking of starting a company?

If you think you can do it, just go for it. That was what I did, even when people told me I couldn’t. But you have to be prepared to pay a price and you are not going to know in advance what that price will be, except that it may be high.

I worked 80 to 90 hours a week for many years which meant having to sacrifice – or at least postpone – some personal things. I only met my husband when I was 40. It’s quite difficult, particularly for a woman. I don’t think it would have been possible if I had had children.

Too much goal directedness can be a hindrance. You can’t plan everything, you can only look for opportunities and be ready to embrace them. I never said I wanted to set up a company. I just found it interesting.

You also need to recognise your own strengths and weaknesses and find the right people to collaborate with. For example, I know I wouldn’t make a good CEO. I need to work with someone who understands how finance works and who is interested in the money.

We all need to find something which aligns with our personality and which interests us intellectually.

Has being in Cambridge helped you?

I’ve had a lot of help from individuals in the University and I’m very grateful to Cambridge Enterprise for all its support over the years, giving me lots of advice and putting me in touch with the right people.

What do you do in your spare time, if you have any?

I used to paint quite a lot but I haven’t had the time to pursue that recently. With the money from the sale of Psynova, we bought a boat which meant I was able to spend six months during lockdown working from a marina in Italy.

Quick fire

Optimist or a pessimist? An optimistic pessimist, always prepared for the worst, but willing to go for it.

People or ideas? I love ideas.

On time or running late? I’m German. I’m always a couple of minutes early. Even when I want to be late, I’m still on time.

The journey or the destination? The destination.

Team player or lone wolf? I’m probably more of a lone wolf, to be honest.

Novelty or routine? I like routine and too much novelty is scary, but after a while I have to break out. I get novelty by switching from an old to a new routine.

Risk taker or risk averse? I hate risks but I will take them in order to move forward. If I could avoid them, I would.

Big picture or fine detail? Big picture, if I have to make a choice, but detail is important.

Do you need to be lucky or make your own luck? You can be lucky once, but if it keeps happening, there’s a reason for it.

Work, work, work or work-life balance? It used to be work, work, work but it’s now work-life balance and increasingly so. It’s important to know when to stop. I certainly will not be hanging around in the University at the age of 70 or 80.

This interview was originally published as part of the University of Cambridge Enterprising Minds series, which was developed with the help of Bruno Cotta, Executive Director of the Entrepreneurship Centre at the Cambridge Judge Business School.

The text in this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License