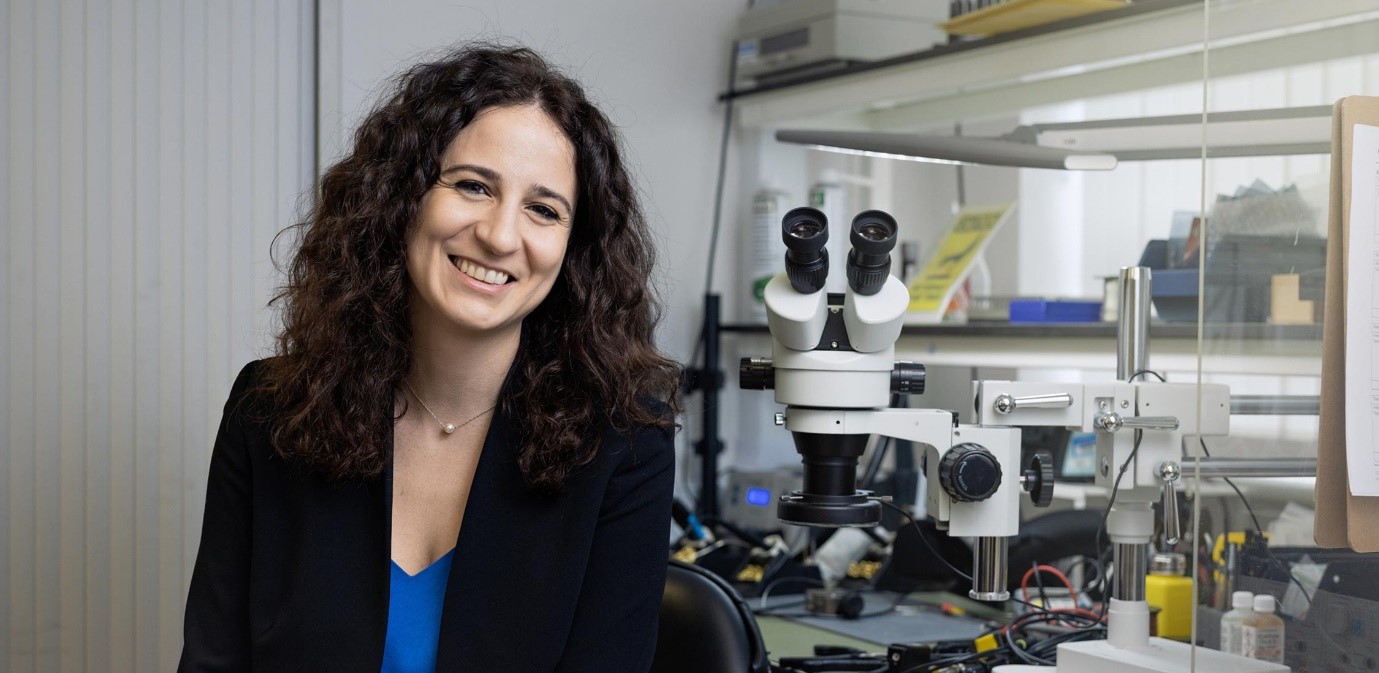

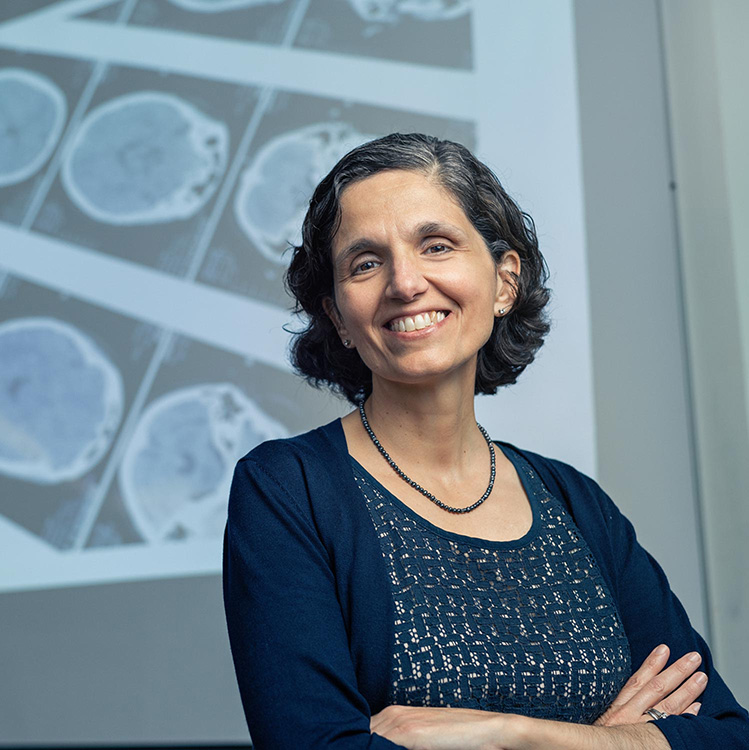

In the latest of the University’s Enterprising Minds series, Professor Zoe Kourtzi reflects reflects on a life shaped by curiosity, cross-disciplinary science and a drive to transform brain health.

The Enterprising Minds series, developed by Sarah Fell with the help of Bruno Cotta, Visiting Fellow & Honorary Ambassador at the Cambridge Judge Business School, explores the different journeys of people trying to change the world and what it takes to bring ideas to life.

WHO?

Zoe Kourtzi, Professor of Computational Cognitive Neuroscience, University lead for the Alan Turing Institute and co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer of Cambridge spinout, Prodromic. A pioneer in fundamental brain science, she is passionate about translating her science into better brain and mental health for all.

WHAT?

Prodromic has developed an AI-driven ‘brain forecast’ technology which can accurately predict how brain disease – including dementia – will progress in individual patients.

WHY?

“If we can tell who is going to have dementia before any symptoms appear, we can make a huge difference to how the disease progresses through lifestyle changes and new medication. That way we can spare families the heartache of losing the person they love to this cruel disease.”

What set you off on an academic career?

I’m Greek. I was the first person in my family to go to university. My parents were part of the generation that came at the end of the war with big families which needed providing for. They had to work from a young age, but they were adamant that I should get the best possible education.

I was good at maths and computing so I originally thought I would study computer science, but my high school encouraged me to take electives in different subjects.

I chose psychology and biology, and it was in psychology that I first learnt about Pavlov’s dogs and became fascinated by the idea that behaviours can be learnt. I went home and told my parents that I wanted to study psychology instead.

At the time, the only place in Greece you could study experimental psychology was Rethymno, a beautiful town in Crete. We had some wonderful visiting lecturers but there was very little published on psychology in Greek at the time. As well as psychology, I was able to take courses in biology, medicine and different types of maths. In a funny, unstructured way I trained myself to be a cross-disciplinary scientist.

My mission is to make sure that the next generation learns how to work across disciplines, but in an intentional, structured way.

What came after your degree?

I applied to do a PhD at Oxford, but I needed to support myself financially. Rutgers University offered me a teaching assistantship and I took it. It was scary. I had never been on a plane before, but they were going to pay me, so I went.

Neuroscience was just starting to happen and Rutgers had one of the first specialist centres. It was an amazing experience but also a huge culture shock. I went from beautiful, safe, Rethymno to a place where there were bars on the windows and you were warned only to go downtown at lunchtime and always to take a friend.

But thanks to amazing support, I survived the shock and finished my PhD. During that time, I had the opportunity to spend a summer in Boston where the first brain scans were happening.

For me, it was a life-changing experience. Even with those early MRI machines, you could see the brain’s activity right there in front of you. After my PhD I went to Boston to study brain imaging, what it can tell us about how the brain works, what happens when it goes wrong, and how it interprets the world around it.

"My mission is to make sure that the next generation learns how to work across disciplines..."

So you were now set on a research path?

Yes. This was absolutely what I wanted to be doing. I moved to a research programme in Germany but continued to go back and forth to Boston.

My work was focused on vision, how we make sense of the information we get through our eyes and what happens when sight is disrupted through age or disease.

Because the brain is so complex, we realised that we needed computational tools to do this properly which took me back to my computer science and maths interests. We were using what we called data-driven approaches 15 years ago, before anyone was talking about AI.

How did you end up in Cambridge?

I fell for British charm! I met my husband – a Brit – and wanted to come to the UK, so I applied to the University of Birmingham, which had one of the UK’s first brain imaging centres. After a few years, Cambridge made me an offer I couldn’t resist.

While I was at Birmingham, I gave a talk about my work and a clinician approached me afterwards to ask me about brain plasticity, whether we can continue to learn at different ages and if we can train the brain to overcome loss. He explained that he had patients coming to his clinic who looked as if they were in the early stages of dementia but he had nothing to offer them. He asked if I could help.

I didn’t know anything about dementia at the time, but we started working on it, even though everyone told me not to. They said not only is it impossible to predict its progression, nobody wants you to, because there is no cure.

By then I had moved to Cambridge and I was struggling to get funding to pursue this research. But the University had embarked on a partnership with the University of Singapore and the University of California, Berkeley to co-fund risky projects. I applied and as well as some funding, I got access to game-changing Singaporean patient data from memory clinics.

For my team, this was a dream come true. We now had lots of high quality, unbiased data on which to test our models. Over time, we got more funding and are now able to talk about prediction and, hopefully, one day, prevention.

My hope is that by being able to detect dementia early and through a better understanding of how the brain adapts, we will be able to delay dementia – to the point of having no symptoms at all – through lifestyle changes alone.

As well as running your research lab, amongst other things, you are also an Alan Turing Fellow, a Royal Society Industry Fellow, and a challenge lead for the University’s flagship AI mission, ai@cam. What drives you to get involved with so many different things?

Research has no boundaries – and you should take any opportunity that comes your way. It’s all about opening doors.

I didn’t come to Cambridge to do incremental science, I came here to do something new. I won’t see the results in my lifetime but I will, I hope, have made it possible for younger researchers to make the next leap forward.

One of the most important things I have learnt, is that to do good science we need input from different perspectives: from patients, from charities, from industry and from people with lived experience. By integrating real-life problems into fundamental science, we can make better, faster progress.

"My hope is that by being able to detect dementia early and through a better understanding of how the brain adapts, we will be able to delay dementia through lifestyle changes alone."

On top of everything else you have now decided to start a company, Prodromic. Why?

From our memory clinics’ study, we have been able to see what has happened to people over a 10-year period.

Our models have proved three times more accurate in diagnosing people and giving them a prognosis than the standard approaches. When I saw how well it is working, I knew I needed to get it out into the world.

Unlike a lot of my peers, I didn’t have a PhD student or post-doctoral researcher in my lab who would have been interested in commercialising the technology, so I decided I had to do it myself.

What are your hopes for Prodromic?

To help clinicians make a confident decision that a patient has early-stage dementia at a point where existing drugs and lifestyle changes can make a difference.

How many families are devastated because the person they love suddenly starts to gamble, becomes addicted to alcohol, loses their job or seems to completely change their personality? Families often tell me they would have treated them in a very different way if they had known it was an illness.

Through Prodromic, we hope we can put our technology into doctors’ hands so they can help both patients and their families have much better outcomes.

Has being in Cambridge helped?

Definitely. Last summer I did the Ignite programme at the Cambridge Judge Business School to help me understand the world of business, which I knew nothing about. It was a week-long course and we got all the theory and background in the morning, then sessions with mentors in the afternoon. It was perfect for me. I came out with an idea of what I wanted to do and in August I registered the company.

But I still wasn’t sure how to start. Then I saw that Cambridge Enterprise had the Founders at the University of Cambridge programme and I applied to that too. It was another intense experience which took me out of my comfort zone but I learnt a lot and got really useful feedback.

Where are you now?

We are at the seed stage, in the process of building the software platform and getting lots of interest.

What have been some of your biggest challenges?

Finding the time! I’m under a lot of pressure to continue my research, to write grant applications. Having a sabbatical gave me the headspace I needed and both Ignite and the Founders programme gave me the confidence that I could do it.

Given your research focus and your recent experience as a new entrepreneur, what would you say makes an enterprising mind?

It’s about bringing your creative spirit, being comfortable with doing risky things. As a society, we don’t always encourage it, but universities have an obligation to help students find and harness their creativity.

"It's about bringing your creative spirit, being comfortable with doing risky things."

What are you most proud of?

Juggling! I’m very privileged to have a job that I love plus a family, with two amazing boys, my lab and all the young people who work in it. To make it work, I’ll be here, there and everywhere on my laptop, or perhaps watching a rugby match while emailing about a research paper.

I love it all, but I used to struggle. There are still a lot of stereotypes about what women can and cannot do, and how you should structure your life. What I’ve learnt is that if you have the drive and the motivation to achieve something, you should not be constrained by other people’s perceptions.

For example, I used to take my kids to Greek school on a Saturday morning and while they were there, I would spend a couple of hours in the lab.

People would knock on my door, telling me I shouldn’t be at work. I found this really hard until a mentor said to me: “You don’t have a work-life balance problem. You are nuts about what you do: that is your life.”

I’m proud of my ability to juggle but I do it with a lot of help: my husband and kids are amazing, and I have a lot of support from great mentors. I am truly grateful to them all for their encouragement every step of the way!

I also come from a family of very strong women and I am indebted to them for their amazing support and inspiration.

My closest aunt passed away from dementia. She had raised her siblings and then her own family at a time and in a country that was very restrictive for women. But she supported me and many others through the strength of her principles.

In the late stages of her dementia, the only thing she could do was to grip my hand. Later, I understood that she was not holding my hand for her own reassurance, she was passing her strength on to me.

“… if you have the drive and the motivation to achieve something, you should not be constrained by other people’s perceptions.”

Quick fire

Optimist or pessimist? Optimist.

People or ideas? Ideas – but it’s people that come up with the ideas and make them happen.

On time or running late? Always late!

The journey or the destination? The journey. I imagine that comes from Homer.

Lone wolf or team player? Team player, a million per cent.

Risk-taker or risk averse? Risk-taker.

Lots of irons in the fire or all your eggs in one basket? Lots of irons and lots of baskets! The juggling can get a bit out of hand sometimes. I really have to stretch to catch some of those balls.

Are you lucky or do you make your own luck? I’d like to think that we make our own luck, but we also carry with us all the influences from our past. I use rigorous methods for making decisions but still there are lots of unknown factors – maybe you call it luck, maybe you call it God’s hand, maybe it’s everything that has shaped us from birth.

Work, work, work or work-life balance? Whatever makes you happy.

This interview was originally published as part of the University of Cambridge Enterprising Minds series, authored by Sarah Fell and developed with the help of Bruno Cotta, Visiting Fellow & Honorary Ambassador at the Cambridge Judge Business School.

The text in this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

All photography: StillVision