Last week, the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee released findings from its inquiry ‘Managing intellectual property and technology transfer’.

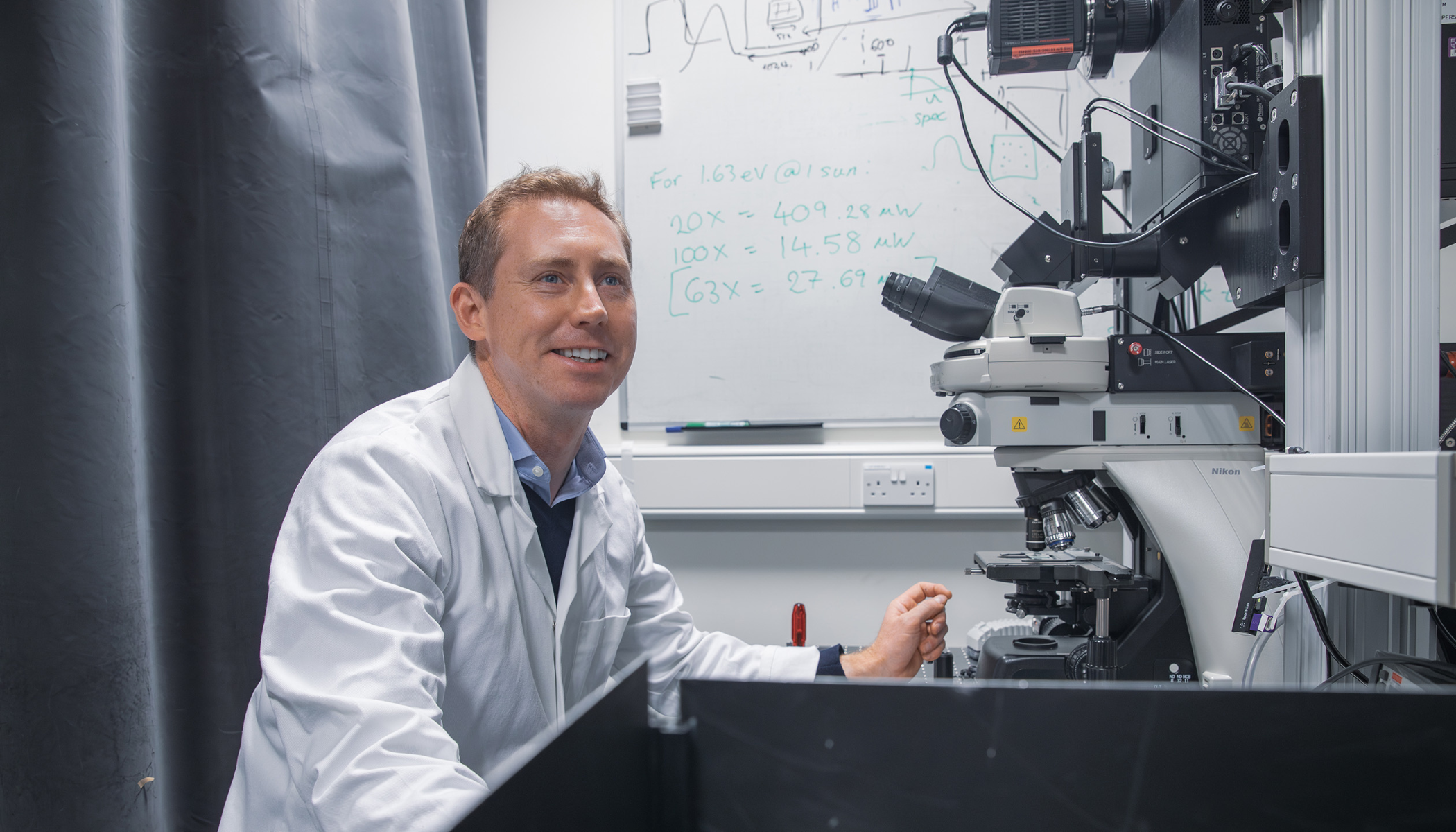

The purpose of the exercise was better understanding how universities commercialise their research. I prepared written comments for the Committee and also testified before it on 2 November. I’d like to share some of my observations.

The first thing to note in discussing UK tech transfer is the very high quality of British universities. Rankings of the world’s top ten universities regularly include three UK universities, including the University of Cambridge. In terms of higher education and research, the UK punches far above its weight.

The second key point is that our universities are also highly regarded internationally for their success commercialising their research. For instance a 2014 MIT study, ‘Creating entrepreneurial ecosystems’, asked a range of experts “Which universities would you identify as having created [and] supported the world’s most successful technology innovation ecosystems”? MIT topped the list followed by Stanford. But coming in at third, fourth and fifth were British universities: Cambridge, Imperial College London and Oxford University respectively.

Despite these (and other) high marks for British universities, there is a lingering view within the UK that our universities lag behind their overseas counterparts. Evidence of this misperception is nowhere more evident than in the number of recent Government inquiries into university-business collaboration. Between 2010 and 2015, the Government conducted nine such reviews.

Last year, John Kingman, chair of UK Research and Innovation, wrote in the Financial Times that: “building our national strength in science and innovation is the best industrial strategy we have in the post Brexit world”. I support this view wholeheartedly.

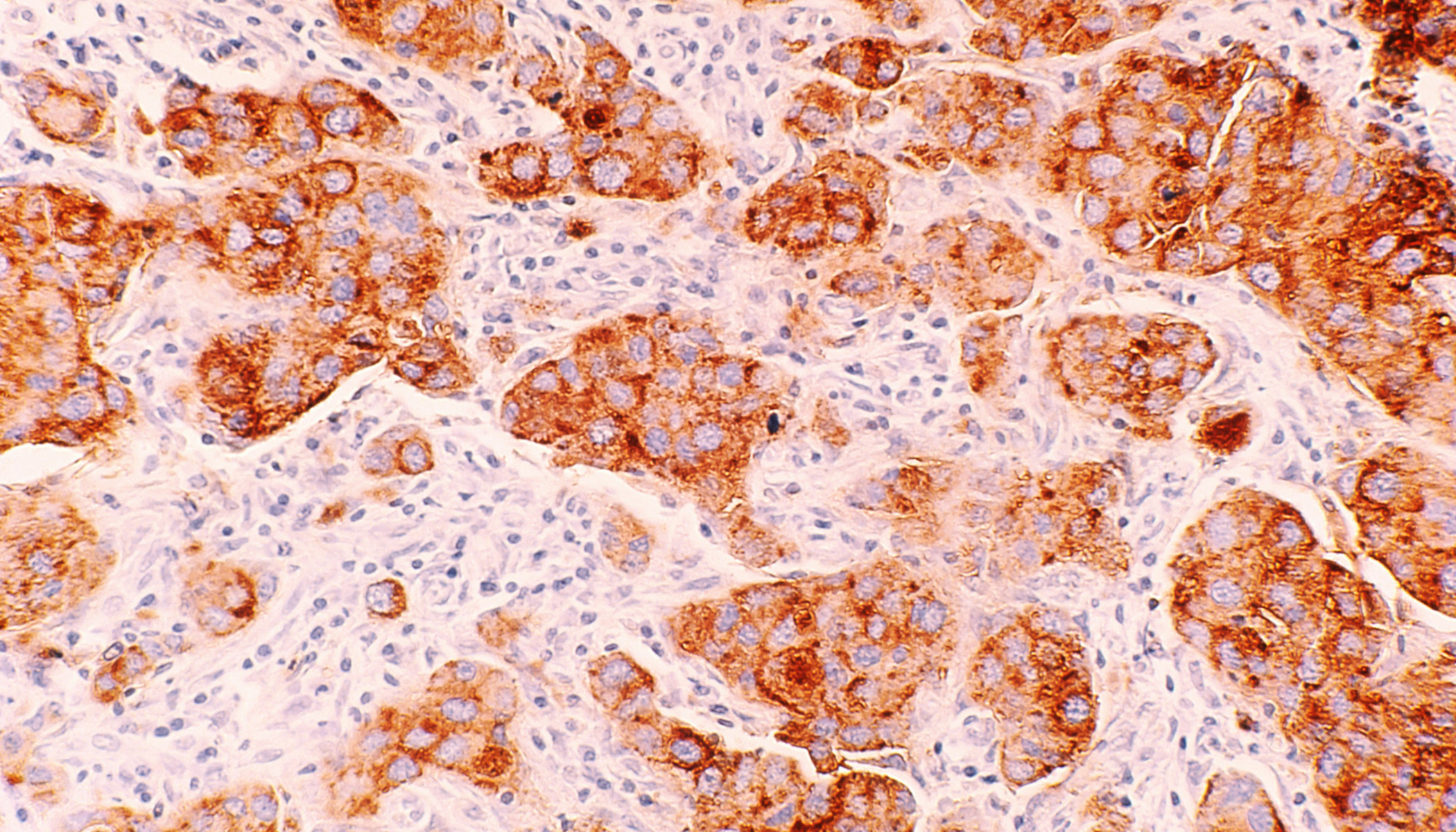

Turning research into commercial success takes two parties, however. It requires a university with a technology to share and a business that wants to develop it. At Cambridge Enterprise, we work with a number of companies that license University research. Some of these companies are located in Cambridge’s high technology cluster, but many are international.

These companies, however, are exceptions. The Science and Technology Committee identified a problem with demand among UK businesses for commercialisation opportunities. This shortfall in demand was pointed out by the Lambert Review of Business-University Collaboration back in 2003 and has remained largely unchanged since.

The Science and Technology Committee concurred with these findings. Compared with other countries, they said, British business is not research intensive, and its record of investment in R&D in recent years has been unimpressive. UK business research is concentrated in a narrow range of industrial sectors, and in a small number of large companies.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) figures from 2015 show that while UK business was spending 1.12% of GDP on R&D, the OECD average was 1.65%, with Germany spending 1.95% and South Korea 3.28%. Measures of innovation output—namely the proportion of companies introducing new, or significantly improved, goods and services—also showed a decline from 24% to 18% between 2008 and 2012 before rising to 19% in 2015.

Taken together, these factors account for a significant part of Britain’s poor productivity growth, a problem recently highlighted by Bank of England Chief Economist Andy Haldane.

How do we start to remedy the situation? The Lambert review urged raising “demand by business for research from all sources”. This point was reiterated ten years later by a 2013 Parliamentary report, Bridging the ‘Valley of Death’, which urged Government to “create a commercial demand for university engagement to which they are already primed to respond”.

Despite these recommendations, the Government’s responses have focused chiefly on the ‘supply’ side of the equation, knowledge transfer by universities, rather than on ‘demand’ from businesses. Until the demand side is addressed, commercialisation will remain challenging for universities.

Stephen Metcalfe, MP, who chairs the Committee, said “Without a healthy commercial demand for R&D, the scope for universities to engage more in technology transfer is limited. Encouraging British business to invest more in UK R&D should be a key goal of the Government’s Industrial Strategy”. I welcome this finding and concur with it completely.