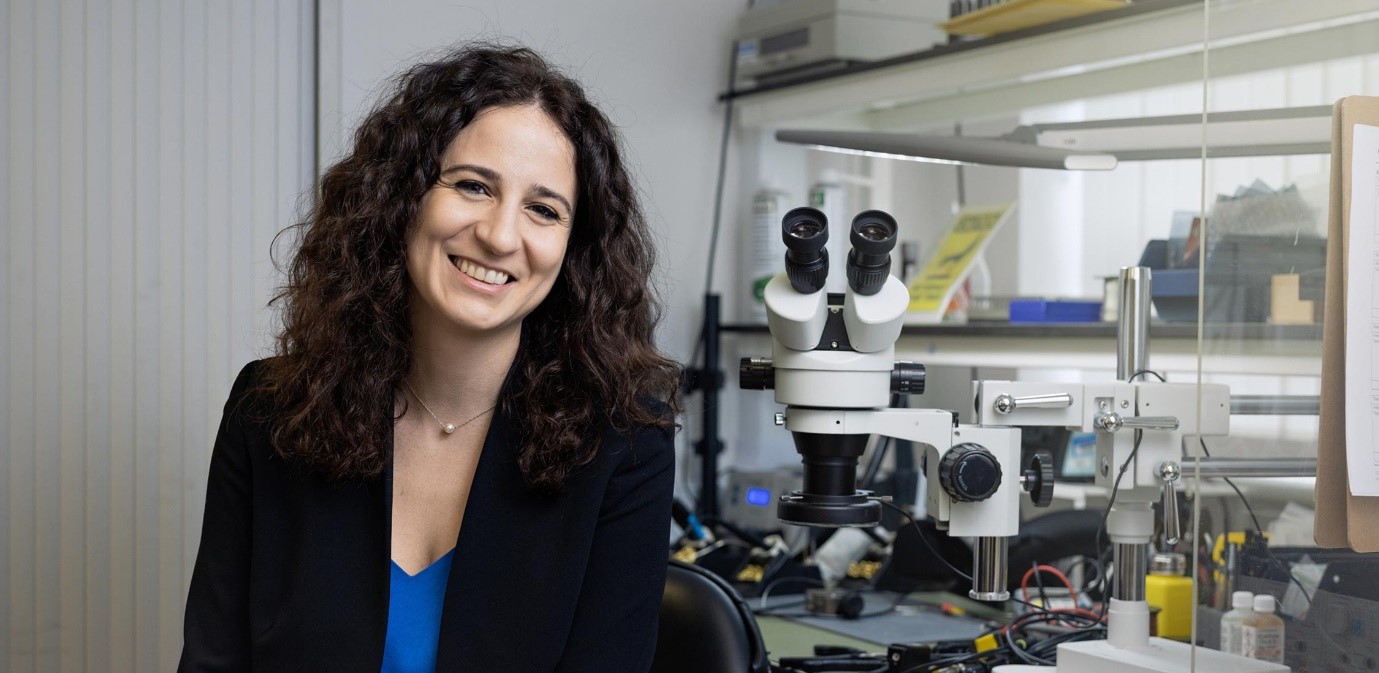

In the latest of the University’s Enterprising Minds series, Kathryn Chapman, Executive Director of Innovate Cambridge, delves into the factors that make Cambridge a hub of enterprise.

The Enterprising Minds series, developed by Sarah Fell with the help of Bruno Cotta, Visiting Fellow & Honorary Ambassador at the Cambridge Judge Business School, explores the different journeys of people trying to change the world and what it takes to bring ideas to life.

WHO?

Kathryn Chapman, Executive Director, Innovate Cambridge. After completing a PhD in molecular biology, Kathryn has had a hugely successful career in life sciences and innovation.

WHAT?

Innovate Cambridge is working with business, government, academia and the local community to deliver an ambitious innovation strategy for Cambridge.

WHY?

To realise Cambridge’s potential as a driver for UK growth and ensure that the economic and social benefits reach everyone, particularly people who live and work in the region.

Were you always going to do something scientific?

My parents were both teachers so education was definitely important in the family but my interest in science came out of the blue.

Growing up, I was a musician, hoping to go to the Manchester School of Music, in spite of my parents’ warning that a career in music can be tough.

Then in the sixth form, I fell in love with genetics. I found it fascinating and wanted to understand more about the underlying causes of disease.

I ended up doing a degree at Manchester University in life sciences and the history of medicine. The history aspect was important to me: I wanted to explore how society affects science and vice versa. But after two years, I realised I wanted to be a scientist and to do that, I would need to focus on a specific scientific discipline to gain a PhD.

At that stage, did you think you would have an academic career?

Absolutely. I loved carrying out experiments in the lab. My PhD was in osteoarthritis – which had affected my family directly – and we found a couple of genes which were linked to the disease. I wanted to carry on and went to Harvard Medical School to learn about a new gene editing technique, a precursor of CRISPR.

What would you say the differences were between the UK and the US research environments at the time?

In those days, it was noticeable that my peers in the US had unlimited ambition and belief. Walking around Boston, there was a feeling you could do anything, that the world was your oyster.

On the other hand, there was an expectation that you need to work long hours, seven days a week. In the UK we have a bit more time to think, to be innovative.

What next?

I came back to the UK as a postdoctoral researcher but began to realise that I could have more direct impact on tackling disease if I was working in industry. I moved to GSK where there was a clearer link between your research and getting drugs to patients.

What were the main differences between being an academic and an industry researcher?

One thing I really liked about working in industry, is that you knew what you wanted to achieve and if you weren’t meeting your milestones you would drop projects. In academia, the tendency is to carry on trying to make it work. I think the ‘fail fast’ approach is really important for innovation.

“…the ‘fail fast’ approach is really important for innovation.”

You then moved briefly to the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and then to NC3Rs – which promotes alternatives to the use of animals in science – as Head of Innovation and Translation. What prompted those moves?

I’m someone who is always looking to make change and have an impact. That’s not always easy in a large organisation.

At the Sanger Institute we were looking at every gene in the genome to figure out what they were all doing. At the time, we were using animals to do this and I thought that was a very inefficient way of working.

When the role came up at NC3Rs, I saw it as an amazing opportunity to work across industry, academia and government, to make research more efficient and effective by using human rather than animal models.

Then you came to Cambridge and joined the fledgeling Milner Therapeutics Institute?

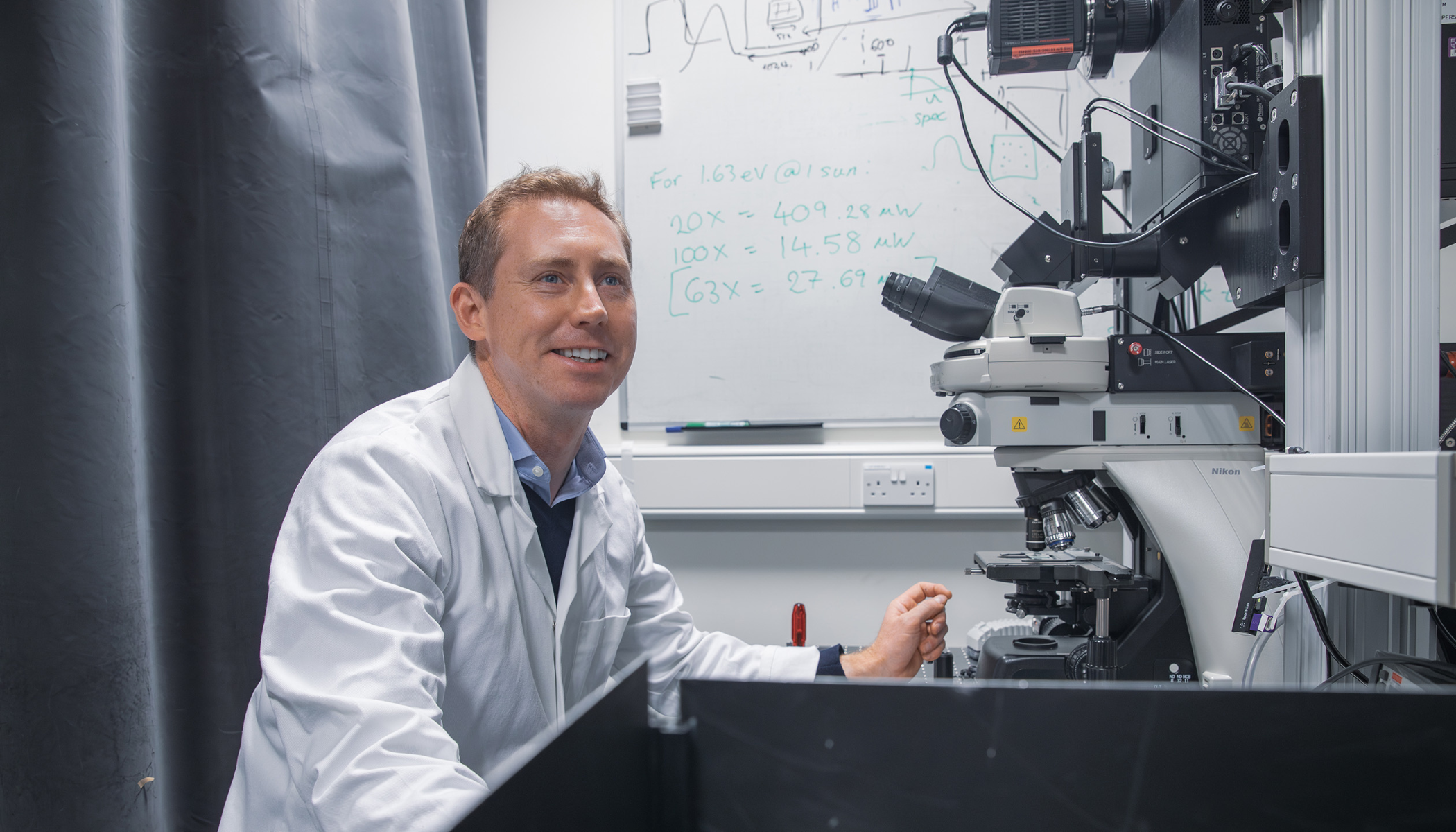

It was such an exciting prospect. We created a new model in which industry and academia could collaborate very early on in the process of looking at disease pathways, with a view to speeding up the drug discovery process.

In just four years, we went from three people in the Institute to 70, working with 15 pharmaceutical companies.

Collaborations aren’t easy. How do you build trust and confidence between people?

I spend a lot of time trying to understand what it is that drives people. Everyone comes to the table with different backgrounds and experience which means they all have different perceptions of the advantages and potential risks of a particular scenario.

It’s trying to understand where they are all coming from and to show how for example, by sharing financial inputs, or pre-competitive data, you can work collaboratively to de-risk a project much more quickly.

When you play a musical instrument in an orchestra, you rely on everyone to get their parts right. It’s the same with innovation.

You need people who have ideas, people who de-risk those ideas and people who put those ideas into practice. It doesn’t work unless you have people with different attitudes and perspectives playing their part.

When an innovation fails, it’s not always to do with how good or bad the idea is. It’s whether you’ve got the right team, the right conditions and the right connections.

“When you play a musical instrument in an orchestra, you rely on everyone to get their parts right.

It's the same with innovation.”

Can you tell us what Innovate Cambridge is and why we need it?

As an innovation ecosystem, Cambridge is competing on an international stage and we have to keep up. We are also delivering innovation driven economic growth to benefit the whole of the UK. There’s no doubt that a lot of our success to date has been a result of our amazing ‘bottom-up’ approach to innovation. But the flip-side of ‘bottom-up’ can sometimes mean ‘fragmented’.

If we don’t work together to achieve critical mass, we won’t attract the investment we need to realise our potential for economic growth and societal impact.

Innovate Cambridge is about orchestrating a strategy that the whole city and region can get behind. And that strategy is not just about driving growth and increasing the number of unicorns but it’s how we go about that in a way that doesn’t entrench inequality.

We want to see innovation benefit us all. Could we, for example, be just as well-known for our vocational and technical training as we are for our academic expertise?

We’ll only be successful if people living in and around Cambridge feel that all this activity has had a positive effect on their lives.

“If we don’t work together to achieve critical mass, we won’t attract the investment we need to realise our potential for economic growth.”

Tell us about Innovate Cambridge’s connection with Manchester?

In the UK, the system for allocating public funding forces cities and regions to compete with each other. We are trying to break that down.

Manchester has a phenomenal amount of talent in areas such as computer science and manufacturing and it has the space for companies to grow. Combine its capabilities with ours and you have something which is greater than the sum of their parts.

If we can make it work with Manchester, it will be a blueprint for how we can work with other cities and regions to grow the UK’s innovation capabilities and create more jobs and opportunities across the country. That’s the ambition.

What are you most proud of in your career to date?

I think it has to be setting up the Milner Therapeutics Institute, we had a stellar team of people creating a new way of doing research in partnership.

What about setbacks?

Accepting that setbacks are part of innovation is the first step. You have to reframe them. It’s a mindset. I see very few things as real setbacks, just as new challenges to deal with.

What would your colleagues say is your greatest strength?

I think they would say that I can get people to buy into a vision. So perhaps it’s the ability to influence and lead.

What does an enterprising mind look like?

Resilience is key but also how they respond to challenges. It’s not always the person who has the most ideas who succeeds.

You need to be able to prioritise those ideas, decide which are most likely to succeed and concentrate on those. Ideas are coming at us all the time and that kind of bombardment can be an innovation killer, if you let it. Enterprising people have relentless focus combined with the ability to know when to stop and move on.

Do you have a piece of advice for someone starting a new venture?

Start with complete belief that you will succeed but remain open-minded about what success looks like.

Finally, what do you do in your spare time?

I stay sane by running 10 km a day, generally very early in the morning. Without that I would struggle.

Quick fire

Optimist or pessimist? Optimist.

People or ideas? People.

On time or running late? Running on time!

The journey or the destination? We should celebrate the destination but the key is to enjoy the journey. Otherwise, why are we doing it?

Team player or lone wolf? Team player, for sure.

Risk-averse or risk-taker? Evidence-based risk-taker.

Lots of irons in the fire or all your eggs in one basket? I think it’s got to be two irons, the main one and then a backup. If you’ve got too many irons, you can’t deliver anything.

Do you need to be lucky or make your own luck? Make your own luck.

Work, work, work or work-life balance? I would say work-life balance but I do work, work, work.

This interview was originally published as part of the University of Cambridge Enterprising Minds series, authored by Sarah Fell and developed with the help of Bruno Cotta, Visiting Fellow & Honorary Ambassador at the Cambridge Judge Business School.

The text in this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

All photography: StillVision