Technology transfer is a bridge that connects academic research and industrial use. Still, the connection is a relatively new and tenuous one.

The slogan “shut up and calculate” was coined in the early 20th century during the great battle of theory and logic between physicists Niels Bohr and Albert Einstein. It underscored the fact that fundamental discovery and industrial innovation are not always aligned. How so? Researchers are often motivated to unravel the unknown, without necessarily thinking of the practical applications of their work. Industrialists, on the other hand, may be motivated by real-world applications – without desiring to understand the underlying complex theories.

For example, as Thomas Edison’s light bulb revolutionised the world by delivering light to our homes and streets, physicists were entirely unaware of the basic theory of the photoelectric effect. The light bulb inspired physicists of the early 20th century to dive down the rabbit hole of subatomic science, giving birth to the field of quantum mechanics (scientific laws that describe the behavior of particles that make up the universe). At the same time, the light bulb inspired industry to transform society – but industrial physicists had little interest in the bizarre and unexplained connection between light and electricity.

The long-term practical outcomes of research may be elusive even to the inventors themselves. Similarly, the industry may be oblivious to the ways in which new scientific theories can change the world. Though technology transfer is a relatively new bridge, every successful connection works to gradually span the divide.

While Bohr and Einstein debated passionately in lecture theatres and in conference halls, the outcomes of their research were spreading like wildfire. Their work led to the understanding of semiconductors – inadvertently giving rise to modern electronics. Advances in communication systems, lasers, medical procedures and nuclear power transformed the world that we live in. Quantum mechanics was so successful that most industrial physicists did not debate its underlying theories – all that mattered to them was the fact that it worked in the industry, and so the slogan “shut up and calculate” emerged.

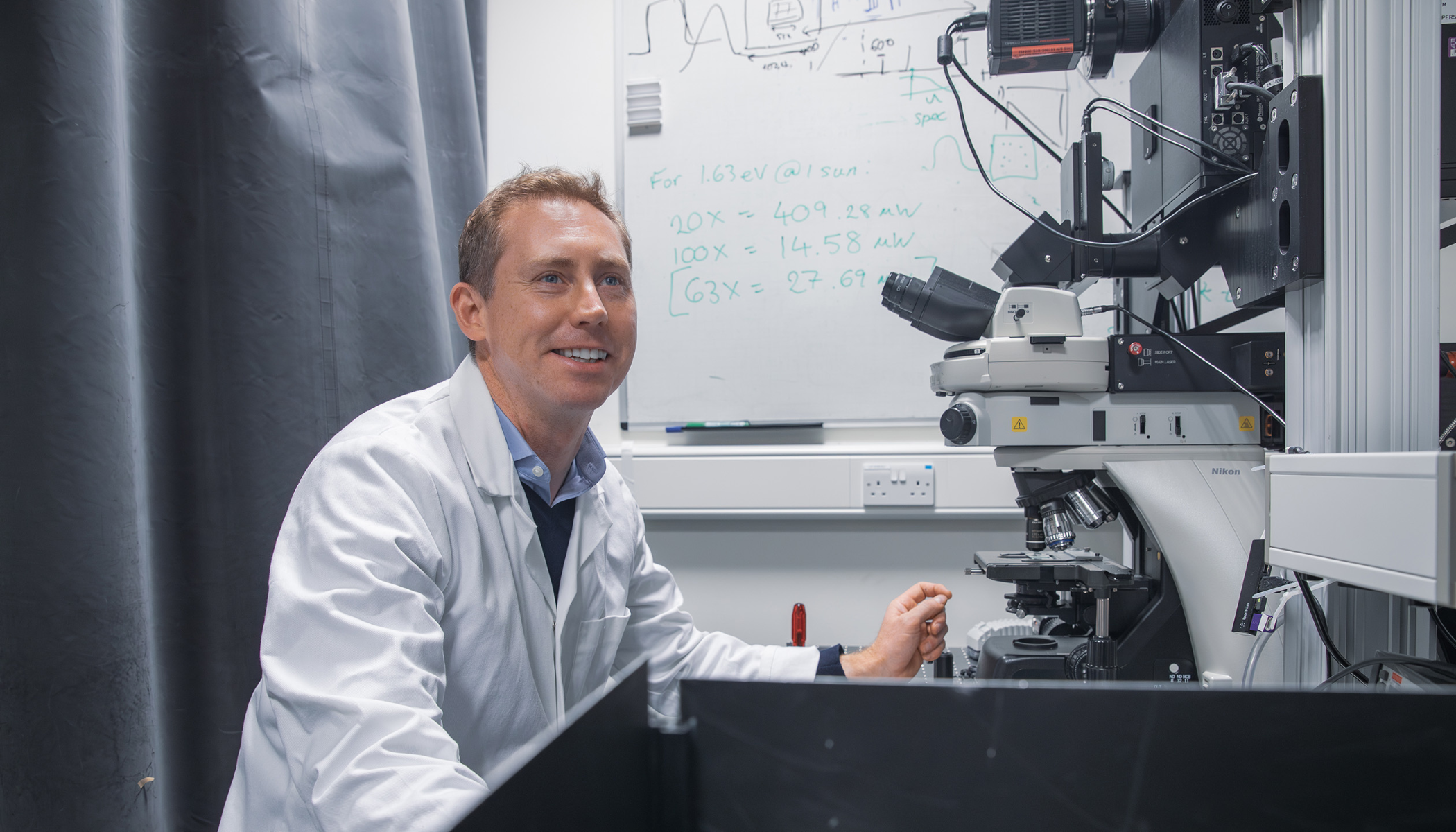

At Cambridge Enterprise, the commericialisation arm of the University of Cambridge, we engage with all Departments of the University. We believe that all researchers have something to gain – and to offer – when it comes to technology transfer. Sometimes scientific knowledge is disseminated and commercialised quickly, for example via licensing technology to an existing company. Other times, a technology may require several years of development and considerable funding before it can be ready for implementation into society. The disparity of these time scales is due to many factors. Sometimes the world isn’t ready to embrace a new technology.

Yet, it is these fundamentally new and sometimes outrageous research findings that can ultimately change the course of history. Incremental improvements are the wheels that make our society and cultures spin, but the real game-changers are based on fundamental research – some of which may take years, or decades, to mature into life-changing technologies.

Take for instance the “Grubbs Metathesis Catalysts,” which were recognised in 2005 with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. These materials simultaneously redefined the fields of chemistry and polymer science by allowing researchers to create complex structures through a specific, relatively simple transformation. Though the first material with real commercial prospect in this area was discovered in 1992, the fundamental research in this field was carried out 20-30 years earlier. It is this lengthy span from ideas to reality that technology transfer works to mitigate.

The long-term practical outcomes of research may be elusive even to the inventors themselves. Similarly, the industry may be oblivious to the ways in which new scientific theories can change the world. Though technology transfer is a relatively new bridge, every successful connection works to gradually span the divide.

It is never too early to share the findings of your fundamental research with our technology transfer office. It is never too early to share the next great idea.

Tags: Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Thomas Edison