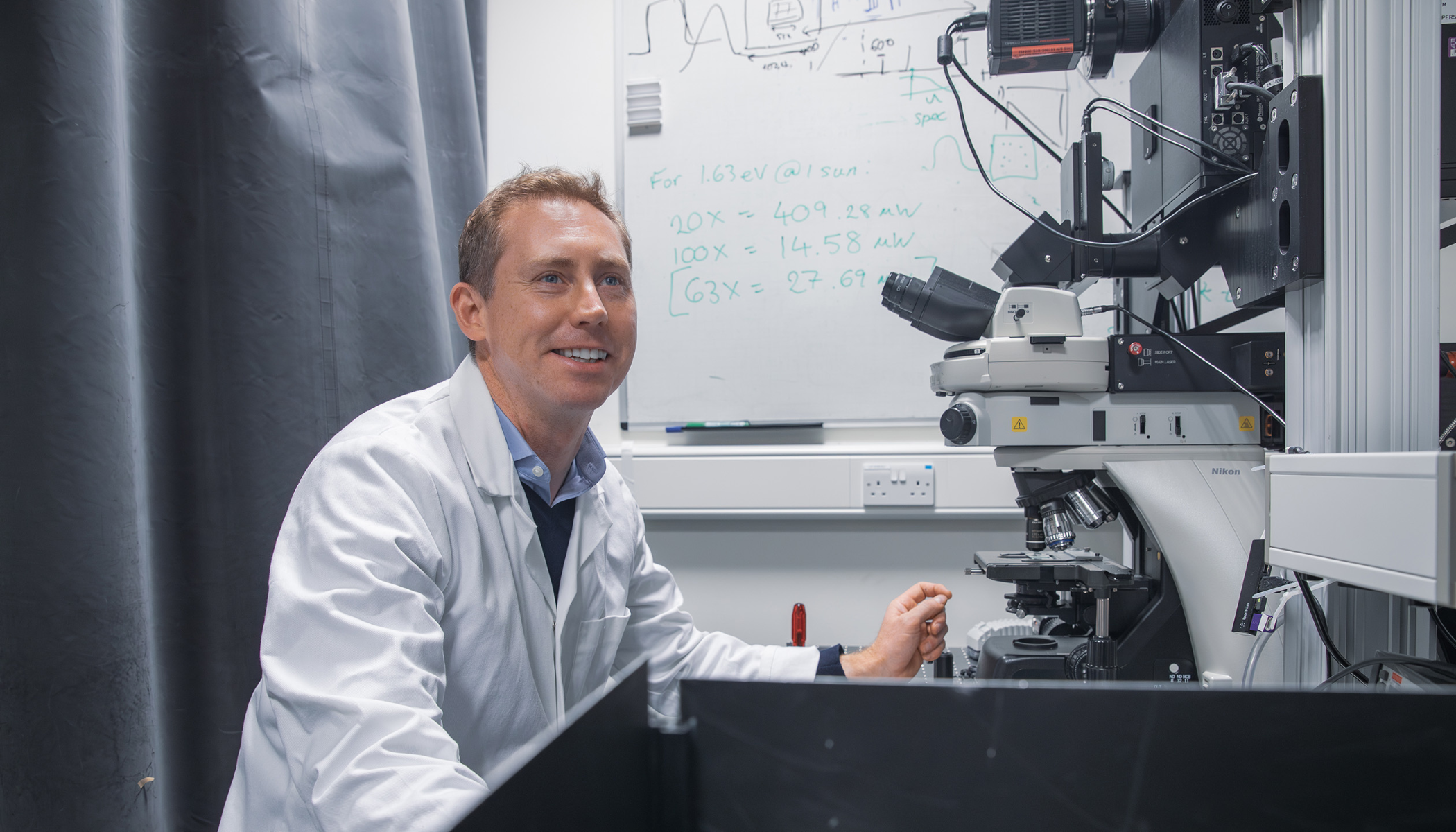

Insights from Professor Florin Udrea

AcademicsIn our 2019 Annual Review, we speak with serial academic entrepreneur Professor Florin Udrea, to gain his insights from his experience as a founder of five companies.

You have an incredible record of commercialising research. Can you give me a summary?

I’ve co-founded five University spin-outs: Cambridge Semiconductor [CamSemi], Cambridge CMOS Sensors, Camutronics, Cambridge GaN Devices and Flusso. The first two have been sold, with tens of millions of pounds evaluation. I’ve also worked through Cambridge Enterprise’s Consultancy Services team for years.

When CamSemi, a fabless semiconductor company, spun out of the University in 2000, it was the first academic spin-out in the power devices field anywhere in the world. Cambridge Enterprise didn’t exist yet. That must have been a very steep learning curve.

Yes. In 1999 Professor Gehan Amaratunga and I met with Richard Jennings, who was the head of Cambridge University Technical Services (CUTS) and Nick Slaymaker, a CUTS director, to discuss a new power device. We’d been researching and developing the technology for 15 years. And we had worked with seven major semiconductor companies, some of which had funded our research, so we had some experience with technology transfer. But the new device was a blue sky invention.

That meeting with Richard and Nick was the beginning of CamSemi. Fifteen years later, CamSemi chips were in 25 percent of all the chargers for Nokia phones. CamSemi would ultimately sell over a billion chips for power supplies.

Academics often are told that forming a company is smart because it protects them from legal risk and gives investors clarity. Is that why you decided to spin out CamSemi, rather than licensing the technology to an existing company?

We weren’t motivated by any of that! All my co-founders and I have wanted to form companies because we wanted to see our ‘academic’ technology put to work in commercial products. We dreamed of revolutionising the world with our ‘avant-garde’ technologies. The original idea behind CamSemi was disruptive, but well ahead of its time, but we kept innovating once we formed the company. Credit should also be given to all the employees who really believed in CamSemi.

"There is always excitement in very fundamental research, there is no question. But there are a lot of interesting things happening when you actually try to translate an idea into practice. Innovation can be at different levels."

What lessons did you learn from CamSemi?

We learned a lot. We were known in the field before as people who are very active in academia, doing our studies using semiconductor simulations or occasionally carrying forward to the proof of concept stage, but never beyond the prototype stage. After we deployed our first products in the market and they became very successful, the community took us very seriously. Suddenly our profile in the field was raised. We were not seen as merely ‘interesting’ academics any more but as successful entrepreneurs who were able to move freely from the academic circle to the industrial stage.

Of course we didn’t do everything right. There were many things we did wrong. We were not used to the world of venture capitalists. We didn’t know, for example, what preference shares were. We didn’t know and, to be honest, neither did the University. We have sort of experimented, and the University was experimenting as well, there’s no question about it.

Can you elaborate on this mutual ‘experimenting’ and learning that CamSemi and the University did together?

For example, there was no University director on CamSemi’s board. The University invested in us right at the beginning, and yet they did not take a seat on our board. Things have changed so radically since then. With my second company, Cambridge CMOS Sensors, Anne Dobrée stayed as a director, all the way from the beginning to the exit. She’s been a great asset. The University director’s mission is to protect the University’s investment and to protect the founders.

Ultimately their mission is also to create value for the University in more ways than just returns to the investment fund. There are so many ways this impact can be measured, which is different from the impact, for example, you create for angels or venture capitalists.

Working in a spin-out company allows one not only to carry out leading-edge research, but also to have access to the resources of implementing new ideas and concepts in sophisticated products, which creates real societal value. Job creation, enabling carrier opportunities, carrying out joint research projects with the University and other partners are other important metrics in the hidden impact of spinning out a company.

As a scientist, have you found applied research less intellectually engaging than pure research? And how does entrepreneurship compare?

There is always excitement in very fundamental research, there is no question. But there are a lot of interesting things happening when you actually try to translate an idea into practice. Innovation can be at different levels. Then from applied research there is the question of how to actually make a business out of it. That’s also an interesting and possibly innovative part.

As exciting as doing fundamental research?

Yes.

Because you’re seeing it actually used?

Yes. Some people have the idea that it’s much more superficial. It isn’t. It’s very exciting, because you have different kinds of constraints. Maybe the analysis is different, but in terms of innovation, in terms of the ideas that are emerging from the applied research to translate to the market, in terms of innovation, it’s as fascinating as research at the PhD level.

So, it wasn’t the money that drew you back to founding companies?

[Laughs] Yeah, another four times! Some people believe that spinning out a company is all about money. It’s not. There is, as I said, a level of innovation that is extremely exciting. And there is something else that happens. In a new company, things move at a very fast speed. In a spin-out things are happening all the time; it’s much, much faster. You see your ideas tried almost instantly. And that allows you to generate new ideas in a cascaded manner. The process of innovation is in fact hugely accelerated. There is also the sense of venture, excitement and team spirit that surrounds a spin-out.

You’re forced to seize the moment?

Yes, exactly. So, it’s not all about making money. In fact, CamSemi honestly didn’t make that much money. It did, however, create so much impact for the University. It raised the profile of our group. It brought many projects to the University, not because the University was famous in the field, but because the company itself became famous. And that’s very, very interesting. And because we had the power to do what the University couldn’t do. The University was able to do very deep analytical modelling and simulations. So, in effect, the company and the University worked extremely well in tandem.

“Cambridge Enterprise is almost like a co-founder because they invest exactly that sort of energy and incredible enthusiasm for the business.”

Professor Florin Udrea

Are there other lessons from your experience with CamSemi you can share?

Money does not necessarily enable things. You need to be careful with the resources used, grow organically and not give up shares immediately. “Do not take preference shares” was a very strong lesson that I learned, and I’m trying to teach that lesson. Unfortunately, at the later stages, other investors and especially venture capitalists want preferences.

The problem is that it makes different classes of shares, which means you are valued less than a later investor is. This is something that I can’t approve of. While they put in money, I put in my time, my energy, my expertise and my soul and this should be as valuable as the money. With Cambridge CMOS Sensors we had one class of shares, and it worked. Investors made a lot of money in the exit. As a founder, I would like to be equal to the people that put money in because I put my effort and my soul into the business.

You’ve used the word ‘soul’ several times.

Yes, that’s a very important lesson. A company needs a soul. Because if you don’t have a soul, in the company, you are not going to succeed. There are a million things which can cause a small company to fail against big competitors. The only chance of succeeding is that strong soul of the founders or the founding team and the team spirit of the employees.

Cambridge Enterprise is almost like a co-founder because they invest exactly that sort of energy and incredible enthusiasm for the business. I experienced that myself with Cambridge CMOS Sensors. In the new spin-outs, Cambridge GaN Devices and Flusso, Giorgia Longobardi and Andrea De Luca are the new souls. Their dedication as founders and CEOs is key to the success of the new spin-offs.

A company needs a soul. Because if you don’t have a soul, in the company, you are not going to succeed.