We recently announced a new investment in Quethera, a gene therapy company that focuses on treatments for glaucoma. Apart from the opportunity to come up with spectacular puns: ‘far sighted investors back glaucoma therapy company’ and the very popular ‘investors set their sights on glaucoma’ (trust me, we’ve tried them all), the news represents an interesting development in the use of gene therapy and healthcare as a whole.

Historically, gene therapy has targeted rare genetic diseases: the therapy replaces a defective gene, one that causes an often debilitating condition, with an effective one. Due to the rarity of the diseases and the ideally one-off nature of the therapy (in theory once the gene is replaced it should last a lifetime), gene therapy is usually very expensive. Health payers can normally absorb such costs and do for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the fact that the need for treatments is few.

The use of the eye as a target for gene therapy has particular advantages:

Consider that the eye is accessible. As squeamish as you may be about getting an injection in the eye – personally it fills me with dread – it’s an easier therapy to administer than one to the liver. And when the alternative is blindness, people would be likely to cope. Sufferers of wet Age-related Macular Degeneration (wet AMD) endure this treatment every month.

The eye is also isolated. Gene products are less likely to migrate to the rest of the body with the potential for deleterious, off-target effects.

This is why a number of companies, such as NightstaRx, are targeting rare ophthalmic genetic conditions.

Quethera, with its targeting of glaucoma, is different in two ways.

Glaucoma isn’t a genetic disease. There are genetic factors involved (familial history is quite well-documented), but it’s not caused by a single defective gene.

Glaucoma isn’t rare. With 500,000 cases in the UK alone it is only going to increase given an aging population.

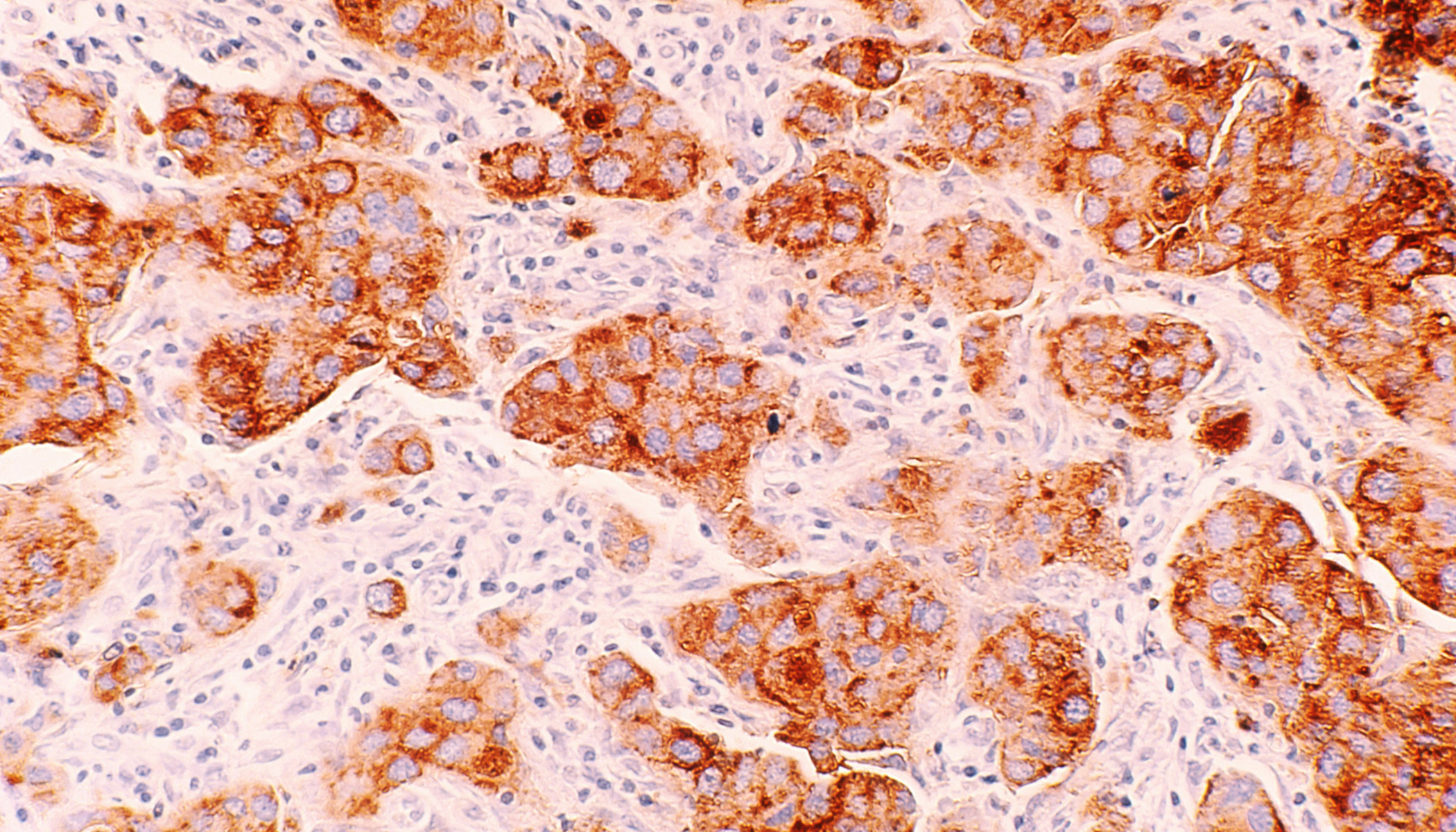

Quethera’s gene products aim to deliver neuro-protectants. So rather than trying to combat the causes of the disease directly, it deals with the ultimate end of the disease, which is death of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), and causes the blindness associated with Glaucoma. These neuro-protectants shield the RGCs from the challenges of the disease and thus prevent blindness.

But what about the use of gene therapy to help glaucoma patients? It’s a mainstream disease with many sufferers around the globe. Treating glaucoma using gene therapy raises interesting challenges for healthcare providers, and, by implication, Quethera.

If a gene therapy costs $1 million and you have only a handful of sufferers in your country, then chances are most healthcare providers will be able to find the funds to pay for these treatments. However, if you have 500,000 sufferers, that would put a considerable strain on any healthcare budget.

Blindness has massive societal and healthcare-related impacts over and above any cost of treatment, so the greater-good argument should be enough to convince providers to pay. But it requires them to think holistically. Famous last words?

I’ve heard speculation about novel ways of paying for gene therapies. For example, rather than a huge upfront cost for a once-in-a-lifetime treatment, health payers pay an annual fee for every year the treatment is effective. Would it work?

Quethera is not the only company targeting common ophthalmic conditions using gene therapy. Oxford Biomedica, for example, is targeting wet AMD using gene therapy.

With more and more companies targeting common conditions using gene therapy, healthcare providers will need to adjust their systems of healthcare provision. Let’s hope they have the foresight (couldn’t resist) to do this.

Tags: gene therapy, Glaucoma, Quethera