Advancing renewable energy and revolutionising diagnostics

Cambridge EnterpriseIn the latest of the University’s Enterprising Minds series, Professor Sam Stranks shares how a passion for science and entrepreneurship is driving innovations in solar energy, medical imaging and education to tackle global challenges.

The Enterprising Minds series, developed by Sarah Fell with the help of Bruno Cotta, Visiting Fellow & Honorary Ambassador at the Cambridge Judge Business School, explores the different journeys of people trying to change the world and what it takes to bring ideas to life.

WHO?

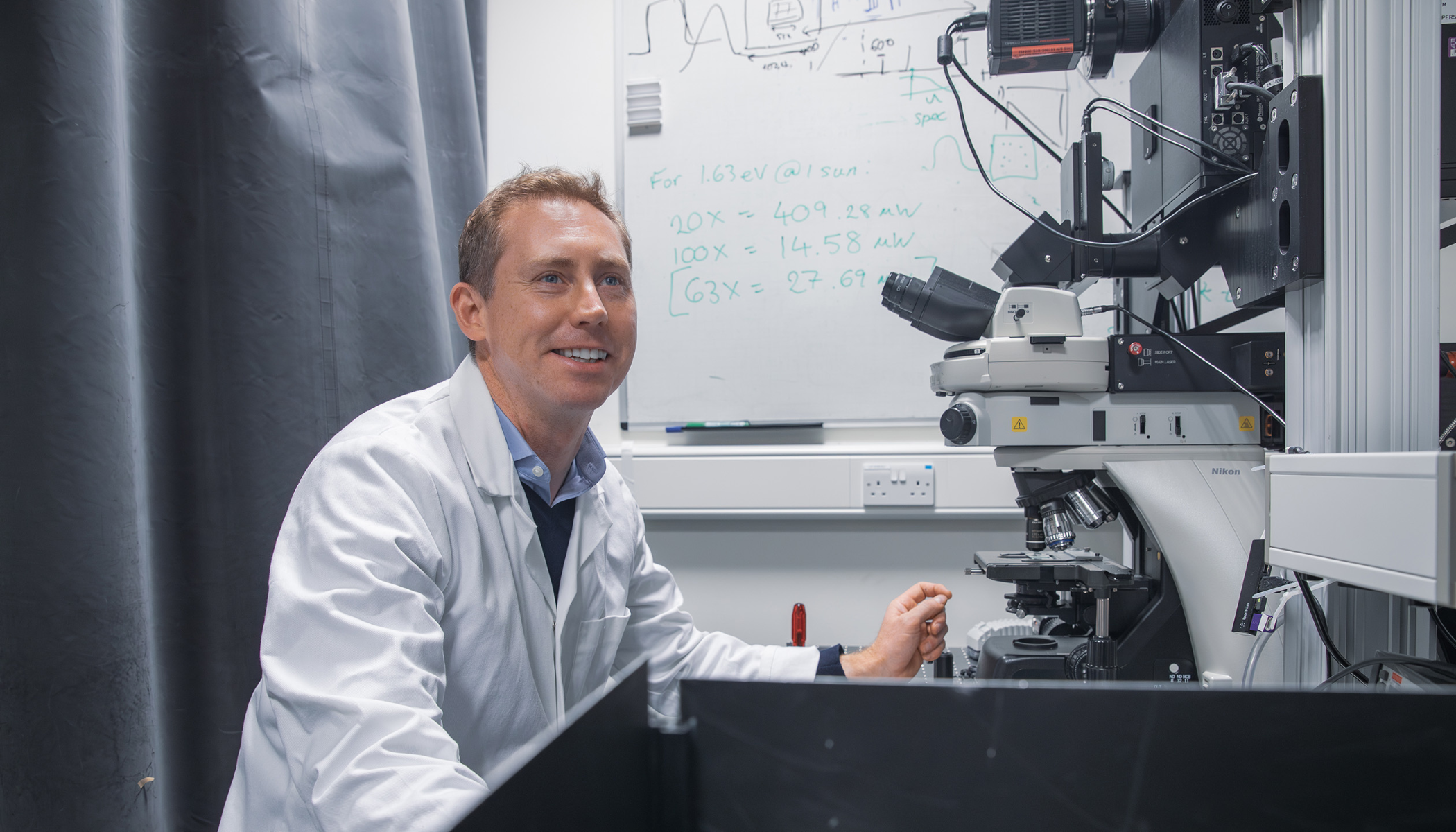

Sam Stranks, Professor of Energy Materials and Optoelectronics at the University of Cambridge and Fellow of Clare College, leading expert in photovoltaics and founder of two companies and an education charity.

WHAT?

Using science to solve some of our most pressing climate and health challenges and helping school children address their climate anxiety.

WHY?

“It’s our duty as academics to try our best to get new ideas and technologies out into the world where they can make a difference.”

What set you on your academic path?

Are you following in any family footsteps? A lot of my family are medics, doctors or physios but my grandfather, Professor Don Stranks, was an academic. Actually, he paved the way for what turned out to be an entirely new field of chemistry – metal organic frameworks or MOFs – for which Richard Robson went on to receive the 2025 Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

My grandfather went on to become Vice-Chancellor of Adelaide University, which is where I studied. Sadly, I never met him as he passed away when I was two, but I always knew about his science and was very inspired by his work. In fact, I was able to cite his research in my PhD thesis which was nice.

Growing up, I just really liked science. I seemed to have an almost natural intuition about how things worked – particularly in physics – and then it was exciting to learn the maths and the theories that explain more rigorously what’s actually going on.

There were two particular aspects of science that attracted me. One was being able to work across disciplines. Even when I was majoring in physics and chemistry, I made sure I was taking lots of other subjects, including things like geology and biology. Unusually, I also did a major in German as part of my undergraduate degree just because I liked studying languages.

The other aspect of science which particularly appealed was seeing how it applied to real life. When physics is taught in schools it can come across as a rather narrow, highly theoretical subject but I was lucky to having inspiring physics and chemistry teachers in high school who showed us what could be done with it.

I guess those two aspects – interdisciplinarity and application – have been constant themes through my academic career.

What came next?

I was fortunate to get a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford for my DPhil and that’s when I started working on emerging solar cell technologies.

After my PhD, I stayed in Oxford as a Junior Research Fellow and began to research perovskites, one of the materials that we are now successfully harnessing for solar power technologies.

Back in 2012, it was just beginning to be demonstrated in the lab and now it’s being manufactured at scale around the world.

It’s been really exciting to see that happen over the course of my career and to have played an important part in its journey.

When did you start thinking about entrepreneurship?

After Oxford, I went to MIT for a couple of years and that’s where I was exposed to the entrepreneurial world and how it intersects with science and engineering.

Before I went to MIT, I had thought of academia and entrepreneurship as separate things, needing very different skillsets. Founding a start-up hadn’t crossed my mind at that point.

But MIT is an amazing environment for entrepreneurial innovation. It seems that every undergraduate has a spinout or some kind of activity on the side.

They are actively encouraged to study and develop ideas outside their core subjects. Cambridge is very good at nurturing entrepreneurship too but MIT has an extra bit of magic about it. It is one of the draws for students applying there.

Is that where the impetus came to start your own company?

I met one of my Swift Solar co-founders there and the other founders were connections from Oxford who had also migrated to US universities. It was during that time that we consolidated the idea for the spinout and launched it.

What did you want to achieve with Swift?

As founders, we were really inspired to develop a technology that would have a meaningful impact on climate change. The idea is to develop large-scale, high-efficiency solar panels using perovskites which can produce between 20 and 40 per cent more power per square metre than conventional solar panels.

“As founders, we were really inspired to develop a technology that would have a meaningful impact on climate change.”

Aside from inefficiency, another problem with the current technology is that although the panels themselves are relatively cheap they are expensive to install. Our solution brings down those costs while generating significantly more power.

How’s it going?

We’ve got a small-scale pilot manufacturing line and are maybe two to three years away from our first product to give us time to further improve and validate the long-term operation.

We know it’s going to be hard breaking into the solar sector because there’s already a cheap technology on the market and it’s going to take time for us to start competing with the incumbents. But if we are successful the upsides in terms of market size and impact are huge.

When you came to Cambridge you chose to keep Swift Solar in the US. Why was that?

Fundraising was definitely a consideration. Particularly in solar, you need to raise a large amount of capital in order to to get to full manufacturing capacity. US investors have deeper pockets, simple as that.

But it was also the case that some of my co-founders wanted to stay in the US for family reasons so, although I was heading to the UK to set up a new lab in Cambridge, in the end we decided that Swift Solar should stay put.

Your next venture was completely different – an education charity. What was the motivation for Sustain Education?

I’d been doing STEM outreach in primary schools for a few years with some of my lab members and we realised that there was a huge problem with climate anxiety.

“Children are being taught about climate change but they are not being told that there are potential technology solutions.”

We wanted to both give them hope and to inspire them to study subjects that will mean they can go on to make their own contribution in the future.

I set up Sustain Education with a couple of my group members to provide teaching modules for teachers. We started by working with the University of Cambridge Primary School to develop materials which we piloted ourselves with a number of schools and which are freely available online.

Based on that experience we developed teaching packs that teachers can adapt and deliver themselves.

What’s the take-up been like?

We’ve had around 3,000 downloads which is really encouraging but we don’t have enough data on how that translates into actual teaching. What we do know is that it being used in at least 20 schools and we have had very positive feedback from teachers and students.

What next for Sustain Education?

We are hoping to raise funds so that we can employ a full-time co-ordinator, which is what it needs to get it to the next level.

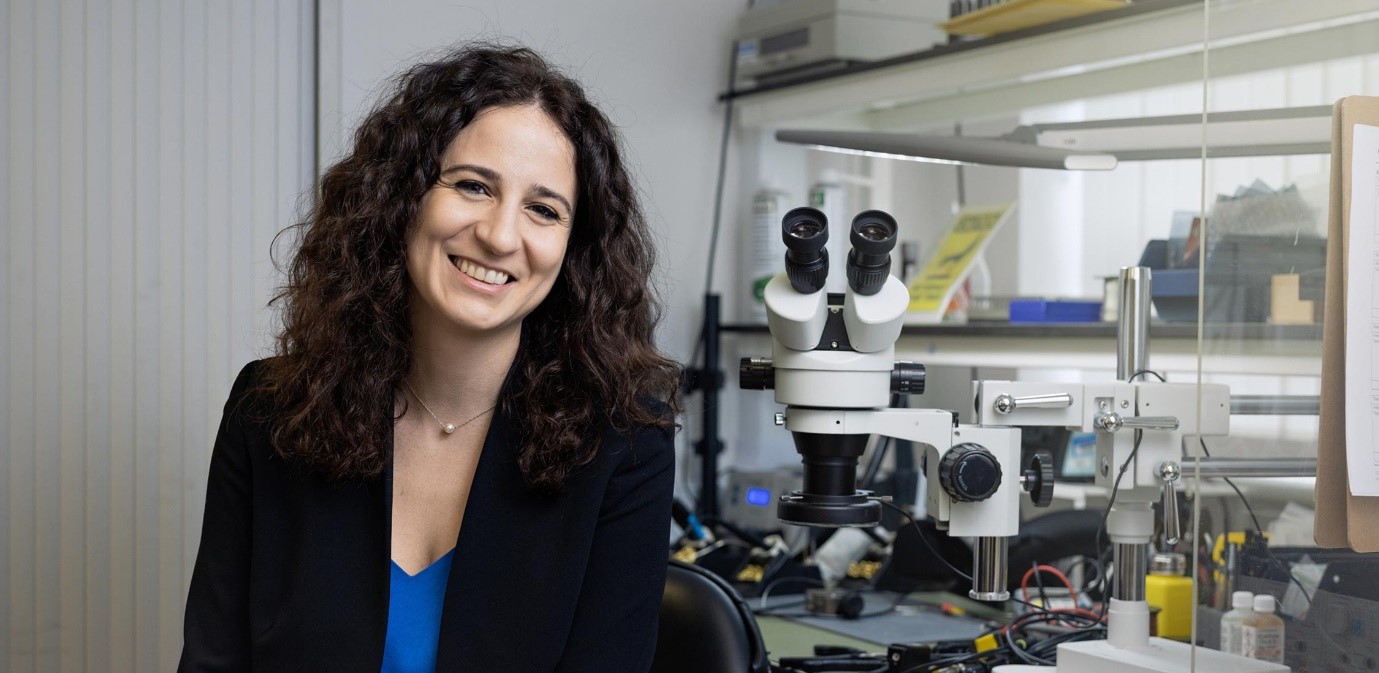

In amongst all this – not to mention, running your own lab – you have co-founded another new venture, Clarity Sensors. What problem are you trying to solve with this spinout?

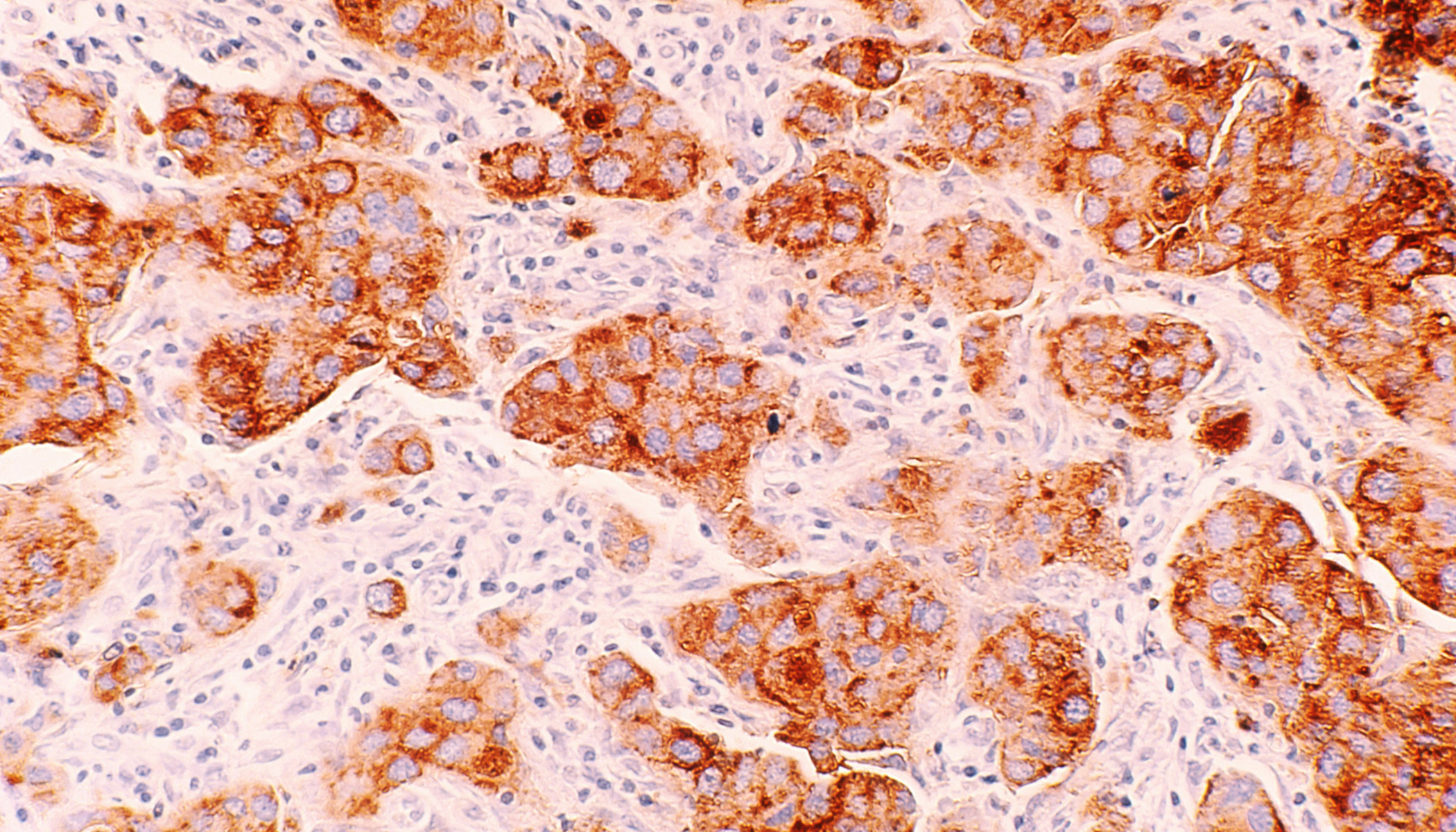

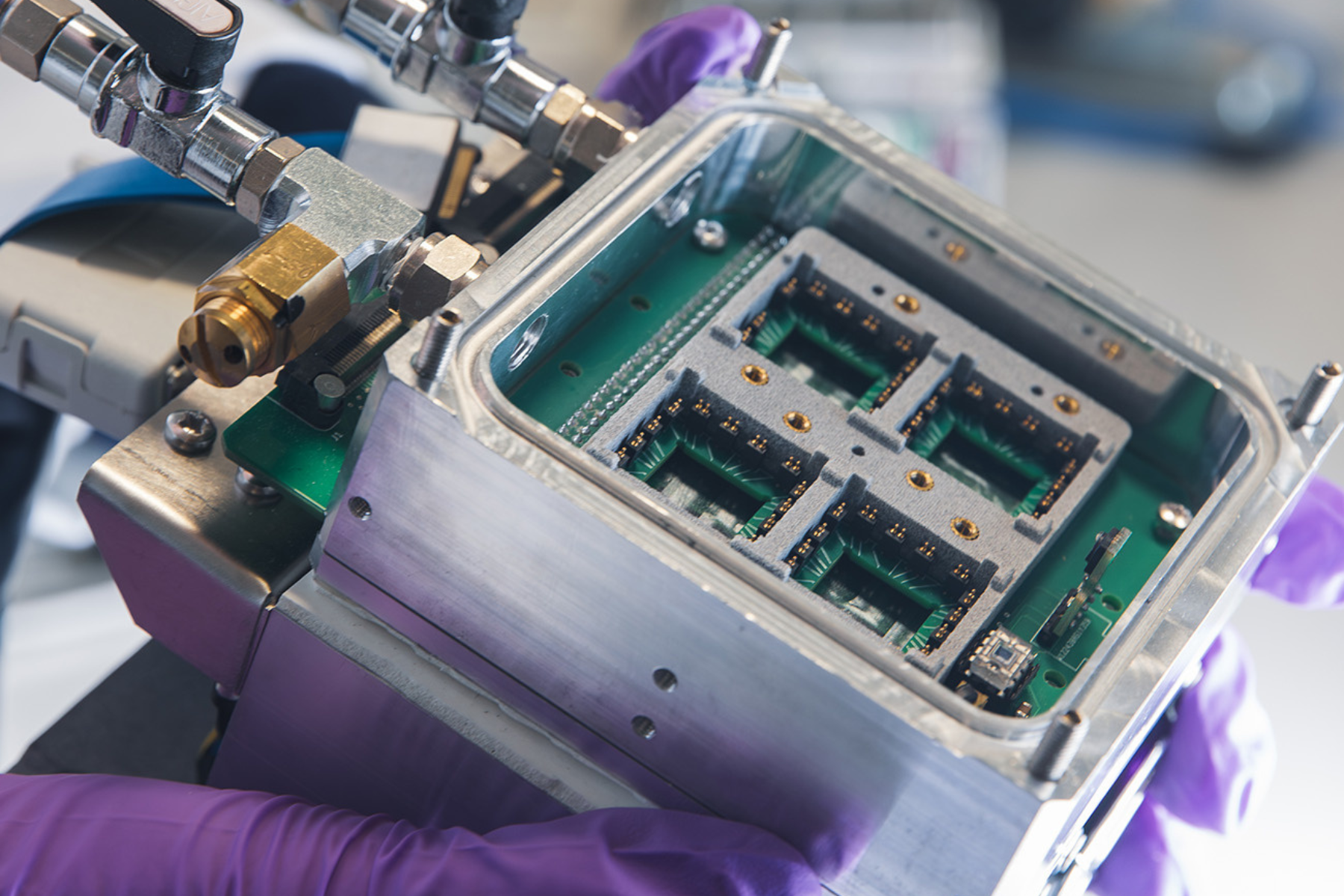

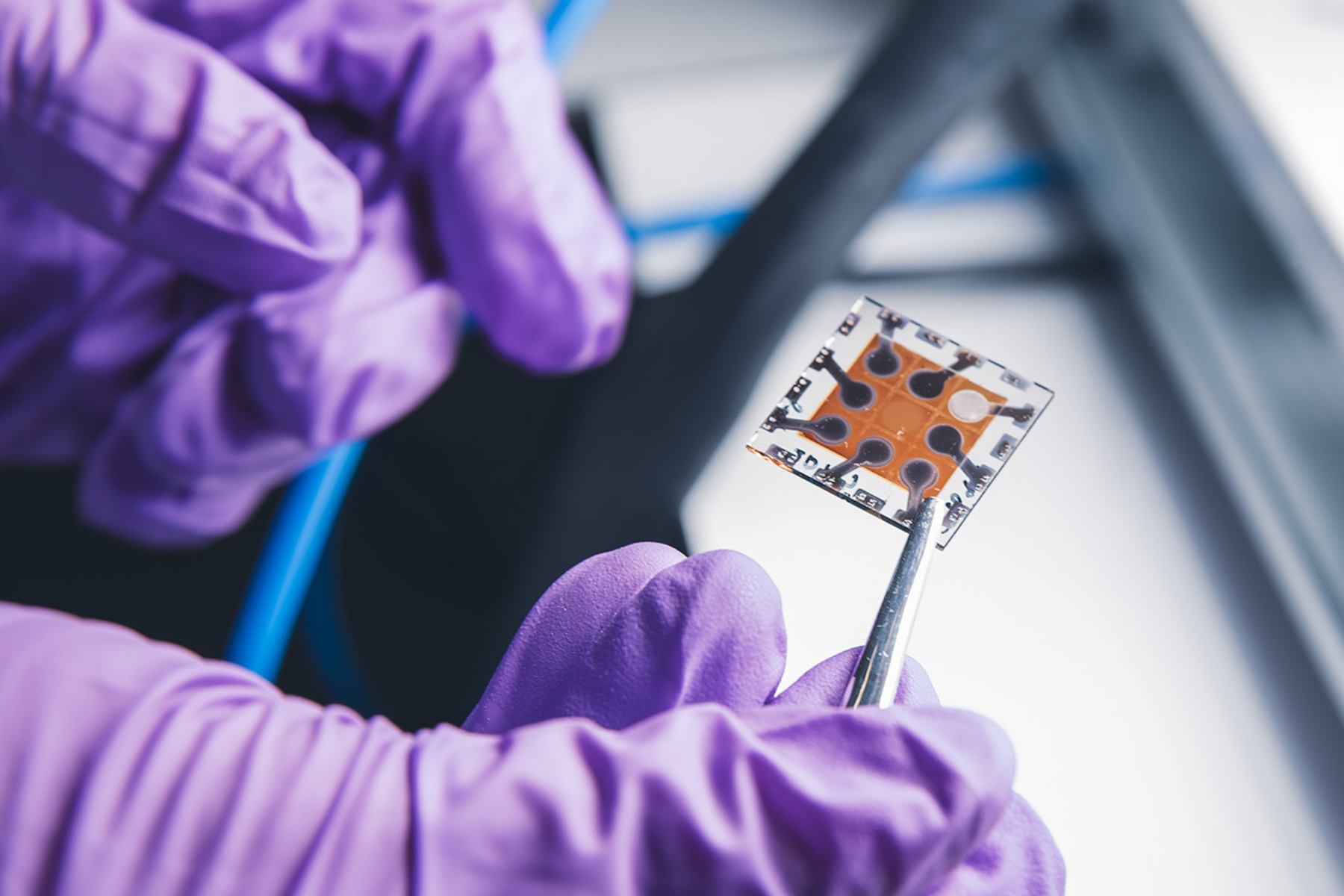

We know x-rays are a vital diagnostic tool in medicine but if they are used too often or at too high a dose, they can be harmful to patients. We are adapting essentially the same technology we are using for solar cells to instead detect X-rays in X-ray scanners. This can produce a new way of scanning patients which provides a vastly clearer image while reducing the radiation dose by around 100 times.

This opens up all sorts of exciting possibilities which could revolutionise medical imaging. Instead of having to weigh up the costs and benefits of an x-ray for every patient, it could be possible to screen whole populations for early signs of disease.

“This opens up all sorts of exciting possibilities which could revolutionise medical imaging.”

Not only is the technology more effective and less harmful to patients, it brings down the costs. To take x-rays safely, hospitals need expensive infrastructure, including lead-lined walls. With our technology, they wouldn’t need that level of protection and scanning could even be done safely in mobile units.

Clearly, there are a lot of steps that need to be taken before this becomes a reality and we are working closely with radiologists to make sure that we are building something that’s fit for purpose.

We have just won a European Innovation Council Transitions grant which has enabled us to hire an operations manager, R&D scientists and a commercial and technical lead, so we are at that very exciting launch phase.

All your ventures have such exciting possibilities. Where do you see yourself – and them – in 10 years’ time?

I hope to be in a position where they are having a real impact on climate change and on human health and that we are able to play a part in helping children and young people navigate the climate emergency and contribute to future solutions.

I’d like to carry on bringing forward new innovations and inspire the next generation of researchers to do the same. I really like bridging the academic and the innovation worlds where we can.

I like to think I’ve created a bit of momentum in my lab around entrepreneurship and innovation. It’s our duty as academics, particularly those of us working in the more applied fields, to try our best to get new ideas and technologies out into the world, whether through licensing or spinouts.

A spinout is not always the right approach. You need the right idea but also the right people to take it forward. There have been times when we’ve thought we had something that had the potential to be commercialised and we’ve started the process but quickly realised we didn’t have people on board with the requisite amount of passion to make it work.

“Failure is something we should be better at teaching our younger colleagues to handle: learn any lessons that need to be learnt and move on. Don't dwell.”

What about setbacks? How do you deal with them?

Setbacks are part and parcel of being an academic. It’s a shock early on when you start to realise that having your grant application rejected is normal. And then it’s the same thing when you get knocked back by investors.

You have to learn not to take it personally. We don’t talk enough about failure and the culture ultimately is still very performance-oriented. It’s something we should be better at teaching our younger colleagues to handle: learn any lessons that need to be learnt and move on. Don’t dwell.

What would your colleagues say is your greatest strength?

Connecting people and ideas, I think. And with ideas, it’s cross-disciplinarity that is so important in arriving at really exciting breakthroughs.

Do you have a piece of advice for a younger researcher who is thinking about starting their own venture?

If you are passionate about it, go for it. But it’s not about trying to get cv-points: you need to genuinely want to do it otherwise investors will see right through you. You have to be prepared for the blood, sweat and tears.

Has being in Cambridge helped you on your innovation journey?

It definitely helps that there’s an entrepreneurial culture here. Obviously, we set up Swift Solar in the US but Clarity Sensors is a much more conventional Cambridge spinout, coming out of my lab and supported by Cambridge Enterprise, which has been hugely helpful.

Do you have any spare time and, if so, how do you spend it?

Mostly as a taxi service for my kids. Seriously, I like to run and play tennis when I get the chance but at the moment it’s really all about work and family, travelling and hiking together when we can. That’s my world and I’m happy with it.

Quick fire

Optimist or pessimist? Half-full, for sure.

People or ideas? People. It’s getting the right people together which ends up making new ideas.

On time or running late? Running late, but not too late. My line would be: on schedule but not on time.

The journey or the destination? Probably the journey but always having the end point in mind.

Team player or lone wolf? Team player – that’s core to who I am and what I do.

Novelty or routine? Both. You can’t pre-orchestrate magic but by doing the routine stuff, you can create the conditions that lets the magic in.

Big picture or fine detail? I’m becoming more big picture over time.

Do you need to be lucky or to make your own luck? I think you make your own luck, by getting involved in something that could be lucky. If there’s an opportunity, take it.

Work, work, work or work-life balance? I do work a lot but I make sure to carve out time for family, friends and the outdoors.

This interview was originally published as part of the University of Cambridge Enterprising Minds series, authored by Sarah Fell and developed with the help of Bruno Cotta, Visiting Fellow & Honorary Ambassador at the Cambridge Judge Business School.

The text in this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

All photography: Nick Safell