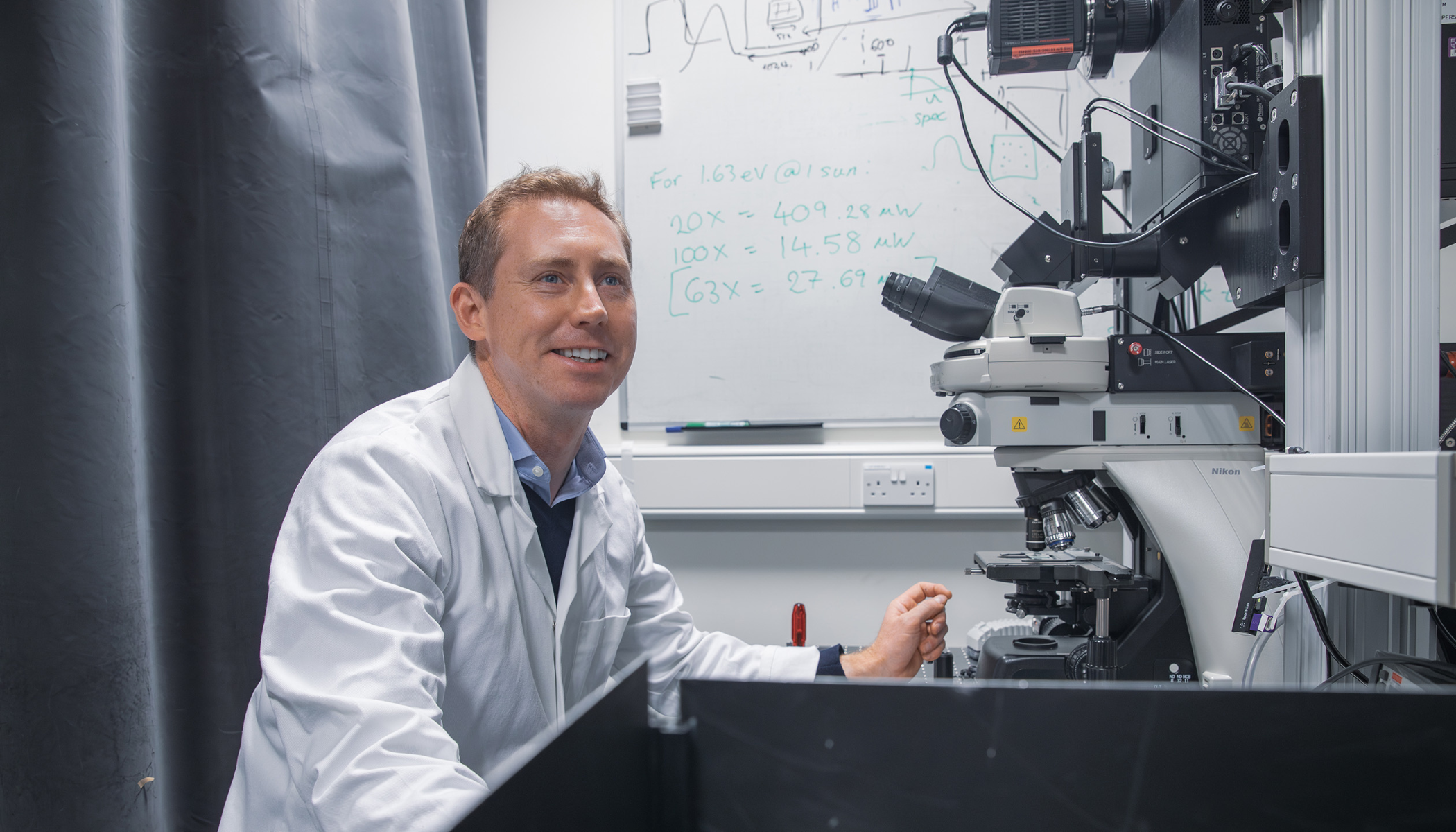

In the latest of the University’s Enterprising Minds series, Dr Jim Glasheen, Chief Executive of Cambridge Enterprise, delves into the factors that make Cambridge a hub of enterprise.

The Enterprising Minds series, developed by Sarah Fell with the help of Bruno Cotta, Visiting Fellow & Honorary Ambassador at the Cambridge Judge Business School, explores the different journeys of people trying to change the world and what it takes to bring ideas to life.

WHO?

Dr Jim Glasheen, CEO of Cambridge Enterprise (the University’s innovation arm), Harvard PhD, investor in life sciences ventures and founder and board member of multiple companies.

WHAT?

To ensure Cambridge innovations have the greatest possible impact on society by building more connections with innovators, entrepreneurs and hubs around the world.

WHY?

“We need the rest of the world to understand the gold that’s coming out of Cambridge.”

What sparked your interest in science?

As a child, I lived 100 yards from a creek and was endlessly fascinated by the wildlife that lived there with us.

Although there was no formal science or medicine in the family, we were constantly fixing cars and bikes. One of my sisters was interested in biology (she’s now a doctor) and she and I would dissect turkeys and stitch them back up before cooking them.

So the fun, practical elements of science and technology were an important part of my childhood and were encouraged by my family.

School was more complicated. I wasn’t a good fit for it. At the end of first grade it turned out I hadn’t really learnt anything at all and was offered the opportunity to do it again.

Things didn’t get a whole lot better as I got older. I probably have dyslexia. I’ve never been good at reading, I have a terrible memory and I’m really bad at multitasking. If I’m writing, I’m not hearing so note-taking is a problem. None of these things are conducive to success at school.

In spite of that, you have had a stellar academic career?

The one thing I do have is focus. My deficits forced me to cultivate this strength: when someone dives into something complex, I’m immediately trying to simplify it, distil it, understand its essence. That became a kind of superpower.

After your PhD you were a postdoc at UC Berkeley. At that point, did you see yourself becoming an academic?

Completely. I was totally committed to an academic career.

What changed?

My PhD advisor, Tom McMahon, was a lovely man but he accidentally ruined my academic future. As well as being a successful scientist in different fields, he also wrote fiction. I watched him do the things that interested him, whether that was research in biology or engineering or writing novels. It was clear to me that he was playing and serving no master. That’s what I wanted to do.

However, it slowly began to dawn on me that this is not how it works for most people in academia. Once you’ve had success in one research area, the forces align to make you stay in that specialty. You write the grant proposal that you are most likely to be awarded – based on your previous work – and your promotion is dictated by the number of grants you bring in. And then you find yourself on a path which it’s almost impossible to stray from.

When the penny dropped, I started to consider other options and applied for a more teaching-oriented role.

At that time, it occurred to me that I should get better at being interviewed as a general skill. It turned out, McKinsey was hosting a reception for potential recruits. I went along and was so impressed that I thought I would apply to learn how to do these business-type interviews.

I continued through the process, figuring that if I liked it, I could always apply again later…once I was better at interviews. But the opportunity was offered and I decided to make the leap straightaway.

What did you learn at McKinsey?

So much but it was a very difficult – often humbling – process. Because I didn’t have a business background, I was never going to be the smart person at the table expounding on strategy or finance.

But I used my time there to learn not only business disciplines, but also more team-based behaviours and crisper communication styles. Thanks to my science background, I was able to establish credibility in healthcare and pharmaceuticals.

I started to specialise in that area and began to see the power of being able to bridge traditional scientific disciplines with business to achieve profound impact.

“I began to see the power of being able to bridge traditional scientific disciplines with business to achieve profound impact.”

How did you make the leap into venture investing?

The late 1990s was a special time when a lot of fascinating science was reaching maturity and starting to have an impact on patients. Seeing the possibilities, one of my clients recruited me to start a venture capital initiative within a corporate finance company.

I seized the moment. It was a great opportunity to build relationships with general partners at various venture firms and to invest side-by-side with them in portfolio companies.

This led to an opportunity to become a general partner myself, co-leading the life sciences effort for another venture capital firm for 20 years. Over that time we invested in numerous medtech, biopharma and therapeutics companies.

Are there any success stories that particularly stand out?

There were plenty of good exits where we made healthy multiples, but one recent outcome springs to mind. Soleno just got its drug approval a little while ago after 20 years of sustained effort through many ups and downs. The drug is one that can treat patients with a rare genetic disorder who – until now – had no therapeutic options. After two decades it has become a multi-billion dollar company.

Alas, I co-led the Series A with a close friend 20 years ago and neither of us were able to hang on for long enough to enjoy that outcome… but the founder did!

Has being on both sides of the fence – as an investor and a founder – been a help or a hindrance?

Having the perspective of both is definitely a help. As an investor, you benefit from having a portfolio and that in turn allows you to take the large risks that are inherent in venture capital and diversify them.

You also can use your broad activities to benefit your individual companies by fostering introductions to talent, partners, and capital. It is a wonderful and privileged role.

At the same time, you are in the boat together with the founder; you can’t just trade in and out when sentiment changes. What you can try to do is turn down the risk a little bit.

As an entrepreneur, on the other hand, you are all in, trying to make your idea work, come what may. It is a rawer experience where the highs are higher and the lows are lower. If wealth is measured by the quality of the dramatic stories you have to tell to your grandkids, then I would suggest most every entrepreneur is wealthy indeed.

What attracted you to the role at Cambridge Enterprise?

Cambridge has a rich history of world-changing innovation and it has done a fantastic job of cultivating a local ecosystem to help get those innovations out of the lab.

But it seems to me there is an opportunity to go further. Cambridge needs to engage more with the outside world. We need to get better at maximising the value of the technologies and talent we have here on a global scale.

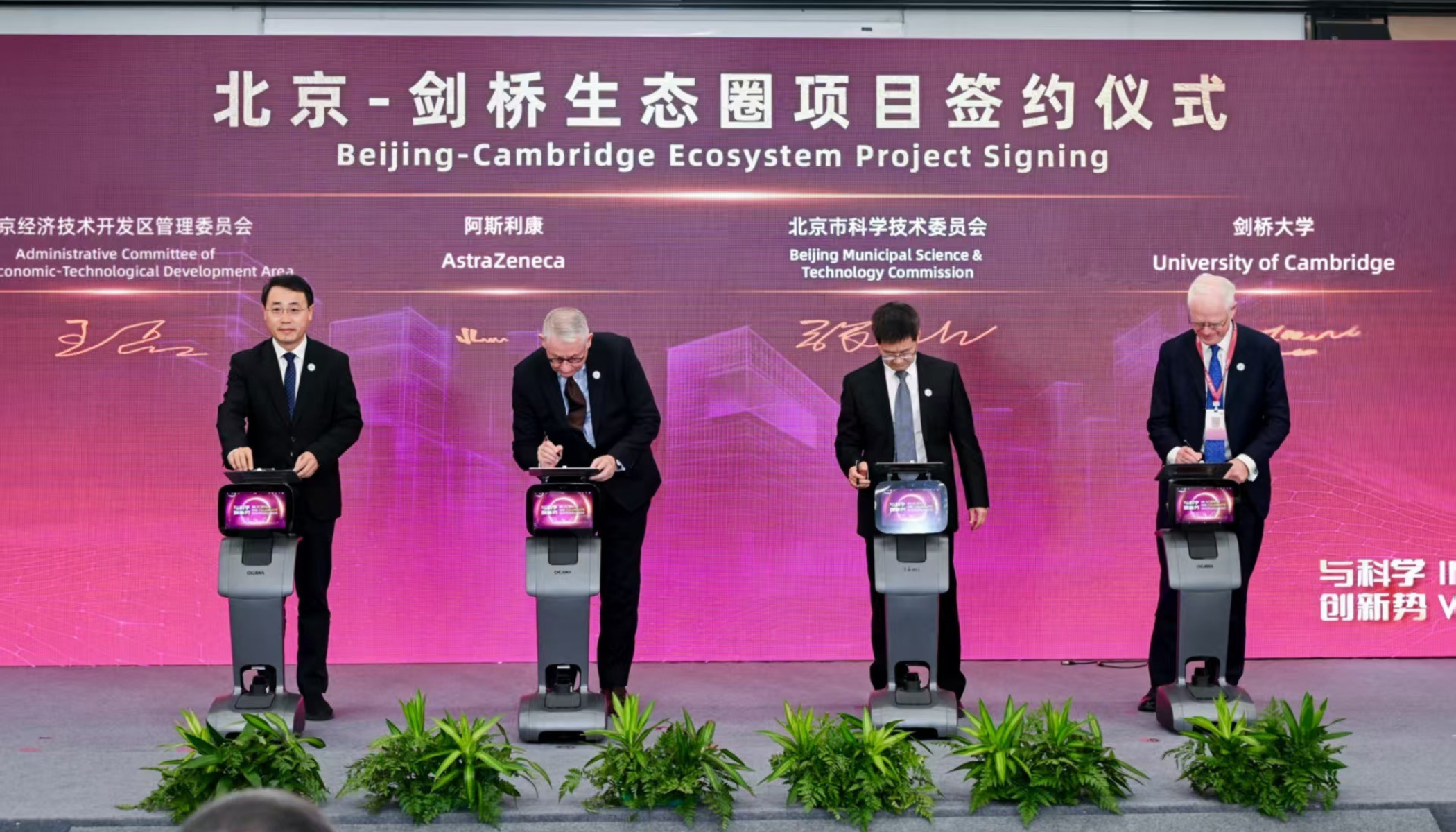

That means linking more effectively with global networks, not only in terms of capital but also in terms of networks of talent and strategic relationships with both partners and customers. It’s all about making connections, bridging Cambridge innovations and people to other hubs around the world.

“It's all about making connections, bridging Cambridge innovations and people to other hubs around the world.”

What do you like about working with academics?

Their quirkiness! The academic personality type is one I’m drawn to. Their refusal to follow rules can be frustrating but it’s also what enables them to unlock fundamental scientific innovations.

Does that mean academics make good entrepreneurs?

Not necessarily. To be an entrepreneur you have to be this weird mix of super-flexible yet also crazily committed. You also have to face up to your own strengths and weaknesses and to understand that you urgently need to deal with the latter by bringing in people to fill those gaps.

As an innovation leader yourself, what would you say is the most effective leadership style in an entrepreneurial context?

Leadership is acknowledging that you’re not doing the work and you often don’t know what questions to ask in order to get the work done.

In the kinds of environment we work in, where things are changing all the time and there is often a lack of clarity, you need to adopt a style which enables you to draw out the insights and learnings from your colleagues. These will inevitably be complex, messy and with irreconcilable differences. Your job is to absorb the knowledge that resides within the organisation and then reflect it back as a clear direction.

“Your job is to absorb the knowledge that resides within the organisation and then reflect it back as a clear direction.”

Do you have a piece of advice for your younger self?

To cut myself some slack. I think many of us hold ourselves up to an unhelpful standard. You need to acknowledge that you will make mistakes – and that everyone will see those mistakes – accept it and power through it.

I’ve also struggled in the past with stepping into the unknown. I was often unprepared and found new experiences difficult to deal with. But I don’t regret embracing those new opportunities, however tricky they were at the time. The things I regret are the opportunities I didn’t take.

Do you have a piece of advice for someone starting out as an entrepreneur?

Invest in your network. I used to think that people who are very networked and use that to their advantage, were somehow cheating.

I now see that’s wrong-headed. Individually, each of us knows so little and we need to connect with people whose insights we value. I’ve come to realise just how valuable my network is and not only that, how enjoyable and easy it is to maintain one.

It can feel uncomfortable to ask someone to do something for you. But if you are always looking for opportunities to connect others with people and opportunities that might help them, growing a network becomes fun and rewarding.

Finally, what do you like to do in your spare time, assuming you have any?

I like to walk, to wander. Nothing is more pleasant than not knowing where I’m going.

Quick fire

Optimist or pessimist? Optimist.

People or ideas? That’s changed. It was ideas, now more people.

On time or running late? I aspire to be on time.

The journey or the destination? The journey.

Lone wolf or team player? That’s also changed. I was very much a lone wolf and am now more of a team player – but with a few wolfish markings.

Novelty or routine? Novelty.

Risk-taker or risk-averse? Risk-taker: I have lots of broken bones.

Big picture or fine detail? Big picture.

Are you lucky or do you make your own luck? So it’s the arrogance of making your own luck versus the passivity of being lucky. I hate the passivity, but I hope I’m not that arrogant.

Work, work, work or work-life balance? Definitely work-life balance but I’m not sure what that means. It’s different for everyone, I guess.

This interview was originally published as part of the University of Cambridge Enterprising Minds series, authored by Sarah Fell and developed with the help of Bruno Cotta, Visiting Fellow & Honorary Ambassador at the Cambridge Judge Business School.

The text in this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

All photography: StillVision